︎ Previous Next︎

Worlds After Wallace

Anna-Sophie Springer, Etienne Turpin

Published 21 June 2016

Among the experts on Alfred Russel Wallace in the English-speaking world,

Dr. George Beccaloni—a former curator of entomology at London’s Natural History Museum, and the Director of the Alfred Russel Wallace Correspondence

Project—is perhaps the most compelling advocate for a reassessment of Wallace’s place in the history of science. His knowledge and excitement are

contagious, and throughout our various visits, tours, and conversations, we

became increasingly certain that our curatorial engagement with the legacy of Wallace was a necessary project to see through, despite numerous obstacles.

During our research, we met with George in his office, while tending to the museum’s insect collection, at his home, and in Epping Forest (one of England’s

oldest), to discuss the significance of Wallace’s collections and the legacy of his work today. What follows is an edited version of these various conversations,

organized thematically (instead of chronologically) for readability. We are grateful to George for his generosity, mentorship, and good humor over the

years. He has helped us grasp the nuances of Wallace’s thought, the importance

of natural selection, and the amazing world of entomology.

A S

Given your expertise, it would be great if you would start off by providing a bit

of context about Alfred Russel Wallace, The Malay Archipelago, and insect

collecting. I would also be particularly interested in how, at the point when the

theory of evolution was formulated, this transformation of knowledge changed

the way that museums were ordered.

G B

One of the predecessors of Enlightenment museum collections were the

Renaissance cabinets of curiosities, which were just assemblages of interesting and strange objects. After

the theory of natural selection was published and people started to accept that species had evolved from other

species, displays became much more

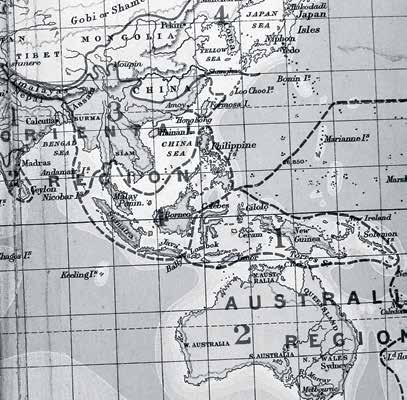

evolution-based. Wallace, as the co-discoverer of evolution by natural

selection, was partly responsible for this. As the founder of evolutionary

biogeography, Wallace was also responsible for another popular type

of display, the faunal diorama, where animals of a particular region are

shown together in one scene. All the taxidermy mammals of the Andes or

the Himalayas, say, are placed together against a natural background showing

some of the habitat. This method of display derives from the plates in

his important book, The Geographical Distribution of Animals. [Fig. 03.]

A S

Let’s step back a bit: who was Wallace and where did he come from?

G B

The basic story is very well known. Wallace was born to a downwardly mobile, middle-class couple in Usk, England (now part of Wales) in 1823. He was educated in Hertford, to the north of London, and had to leave school when he was only fourteen. Charles Darwin left school much later, when he was sixteen, and then went on to two universities. After leaving school Wallace educated himself from books and also attended working men’s clubs. He became interested in natural history whilst working with his brother as a trainee land surveyor, travelling in the countryside of southern England and Wales. His first interest was botany, as he wanted to identify the plants he saw whilst out surveying. He bought his first books on the subject and realized that there was a whole science behind the classification of plants and animals. He formed a collection of pressed plants in order to remember which species he had seen before and more accurately identify them from the books that he read. He then got a job for a year as a teacher in Leicester. That’s when he met Henry Walter Bates, a keen beetle collector who got Wallace passionate about insects. Wallace then returned to Wales and started collecting beetles, moths, and butterflies.

E T

Was entomology a fairly common

practice

at the time?

G B

Yes, there were many entomologists at the time, and they published their

records and observations in various

specialist journals, just as they do today. However, entomologists formed a

tiny proportion of the population, then as now. Most people think you’re

weird when you tell them you collect beetles, and probably the same was

true back then.

E T

Do you know how long this amateur

scientific community of entomologists was working before Wallace’s time?

G B

The number of amateurs studying

insects increased steadily from the mid-eighteenth century, and as a result

the insects and other fauna of Britain were pretty well known by the time

Wallace began collecting. By the 1850s natural history had also become very

popular among the general public. A friend of mine, the writer and artist Errol Fuller, who is interested in the history

of taxidermy, has said that everyone had to have a stuffed bird in their living

room at that time. So, there was a greater appreciation of and interest in

natural history, and a huge demand for showy foreign specimens to display

domestically—butterflies on the wall, or a stuffed bird. However, Wallace’s

market—the people who did serious scientific work on the collections he

sent back from his expedition through the Malay Archipelago (1854–62)—was

really just a handful of people. There were probably more amateurs doing

the serious work of describing species in Britain than there are now, but that’s

not the case everywhere. In Eastern Europe, for example, there are still many

amateurs doing that sort of work.

A S

Did the majority of specimens that

Wallace sent to Europe from the Archipelago end up in private

or public collections?

G B

Probably less than fifty percent were purchased directly by the British

Museum. Wallace mostly collected insect and bird specimens, and he

shipped them to his agent, Samuel

Stephens, in London. Stephens

had rooms near the old British Museum (the natural history collections that we have here in South Kensington used

to be in Bloomsbury, in what’s now the British Museum). When new shipments

came in, Stephens would let the scientists in the museum know, and

they would come to pick out all the things they thought were interesting or new. The rest of the material was then

sold to keen amateurs such as William

Wilson Saunders. Saunders would

take all of Wallace’s smaller orders of insects, whereas the beetles went

to certain specialists on the different

groups. For instance, Francis P. Pascoe got the longhorn beetles. Stephens

often kept some specimens aside for a certain collector. Then there was

the general public, who had very little

knowledge of natural history but wanted really showy specimens—

brightly colored parrots or hummingbirds or whatever—to decorate

their

homes. We don’t know what proportion

of specimens went to the third group of people because typically the

original labels were removed. Even if you went through collections

of old Victorian taxidermy today (and

there are many such collections), you wouldn’t know if they were Wallace

specimens or if they were collected

by someone else.

E T

But there was a certain accounting

procedure, was there not? Everything had to pass through Stephens,

who would have had some form of

master list to track payments owed to Wallace, no?

G B

Wallace kept rough records of how

many specimens and species he collected on each island and shipped

back to Stephens. His notebook

detailing his consignments to Stephens is in the Linnean Society library.

Unfortunately, however, Stephens’s

records do not survive.

A S

Are there any shipping papers

or transportation documentations

available?

G B

None that were issued by the actual

shipping agents, at least none that anybody has ever found. Maybe

Stephens had lists but they don’t

survive at all, so we only have fragmentary information, and we don’t even

know exactly where most of Wallace’s specimens are now. We have a fairly

good idea which museums have Wallace specimens in their collections,

but we generally don’t have lists of the specimens they have. Although I’m pretty sure that there must be

thousands of Wallace specimens in the Paris museum, there’s no list of them

and no way of easily finding them. This is also true in the Natural History

Museum, because our specimens haven’t been individually databased,

and won’t be for a very long time, if ever—the collection is just too huge!

We have about 25,000,000 insect specimens; although we don’t have a record of what Wallace specimens

we have, I have estimated that we must have roughly seventy percent of

everything he collected. Our museum not only purchased Wallace’s specimens

directly from Stephens, but many others came in collections formed by entomologists which were purchased,

donated, or bequeathed to the Museum when the collectors died.

The Oxford Museum of Natural History has the second biggest collection of

Wallace’s specimens, mostly insects. Sadly, in the whole of the Malay Archipelago there are only two Wallace

specimens—a dung beetle in the Sarawak Museum in Malaysia and

a drab little bird in the natural history museum in Singapore.

A S

So what first made you interested

in Wallace?

G B

When I was doing my Ph.D. on the evolution of mimicry in butterflies from

South America, I became interested in theories of animal coloration—for

warnings, camouflage, sexual selection, and so on. I realized that it was Wallace who proposed the majority of these

theories. I hadn’t really heard of him before, nor did I know that he was the

co-discoverer of natural selection, so I started to read a bit more about him.

I was reading James Marchant’s Alfred Russel Wallace: Letters and Reminiscences,

which says that Wallace was buried in Broadstone, Dorset, on a windswept hill. On the first outing that

I had with my wife-to-be, we happened to be camping in that area of Dorset

and I had just read this, so we ended up going to find Wallace’s grave.

After some searching, we eventually discovered it behind a huge conifer;

it was marked by a strange monument, which looks a bit like a phallus on a

stone base. I decided to find out who owned

it because I felt it was a shame that it was in such bad condition—you had to

climb inside the tree in order to see the name plaque, and the roots were

tipping it over. I contacted the cemetery

and they said that Wallace’s grandsons still owned the grave—I hadn’t realized

that any of his grandsons were still

alive. I managed to find the address of

his grandson Richard and wrote to him, saying that I’d seen their grandfather’s

grave was in a sorry state. He wrote

back saying something like, “Yes, it’s a

great shame. We do our best, but we’re

72 73 getting kind of old and we go there once

a year to clear shrubs and brambles

from the base.” As Wallace is one of the

greatest figures in the natural sciences, at least in biology, I decided that his

grave should be restored. I started the

Wallace Memorial Fund in order to raise

the money to do this and extend the lease on the plot. I’d discovered that the

lease only had another fourteen years to

run, after which time they would use

the plot for another burial and dispose of the monument.

I sent articles to various places

telling them about the fund and that I

was looking for donors. Within a pretty short time we had over 100 donors from

all around the world, which enabled

us to restore the monument, cut down

the tree that was pushing it over, put up a new bronze plaque explaining who

Wallace

was, and extend the lease

on the plot. By this stage I was in touch

with various people in places where Wallace had lived and they were really

interested in participating; working

with them, we set up other monuments.

A S

Tell us more about how Wallace collected

and identified his 125,660 specimens?

G B

There are actually people who know

very little about natural history who

think that Wallace had an easy time,

that he sort of just picked out the insects that flew into his hair as he wandered

around. In reality, how Wallace

went about collecting was an incredibly

skilled practice that very few people in the world could do as well as him,

even today. He was primarily gathering

specimens for his private collections.

He always made that very clear, both in his work in the Amazon and

in the Malay Archipelago. He was very

interested in geographic distribution

from early on, and wanted specimens of many species of insects and birds so

that he could study them back in Britain.

Whenever he collected a species

for the first time, he would keep the first specimen or two for his private collection, and only when he had duplicate

specimens would he sell them.

We know he didn’t collect many of the same species because it wouldn’t

have made sense financially. He must

have had an incredibly good memory,

and not having a camera he had to remember each and every species he

collected so he wouldn’t collect them over and over again. He was able to

identify most of the bird species he collected using a book he had with

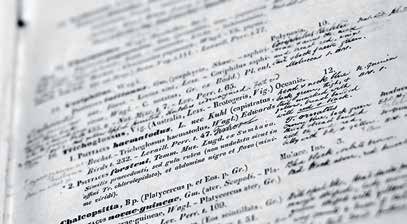

him: Lucien Bonaparte’s Conspectus. [Fig. 02.] Rather incredibly, this book has no pictures in it, only brief Latin

descriptions of the birds. Even today

a top bird specialist would find it incredibly difficult to use a book like that to

identify species in the field. But Wallace

obviously had a remarkable grasp of the distinguishing characteristics

of birds, and using the brief descriptions

in this book, he was able to visualize exactly

what the species looked like.

Even if you have a modern bird book

with photographs or illustrations, it is difficult enough to determine what

you’ve seen. Yet we know that Wallace

accurately identified many birds and realized which were yet unnamed

species. He named and described

a lot of the new species himself, and sent off others he believed were

new with instructions for Stephens.

Often Stephens would then contact the bird people at the museum

and they would buy and name them.

For insects, all he had was a book that described the known species of

two families of butterflies: Pieridae and

Papilionidae. It was in French and had no illustrations, yet as with his bird book

he was able to identify most of the

butterfly species he collected. With all the other insects, he memorized what

they looked like when he collected

them. I have a good memory for that too, and can remember nearly all of the

insects I have ever seen—the interesting

ones at least! Because Wallace had a photographic memory, he could

remember all the species of insects

from each island without having to assign scientific names to them. Since

most of the insects he was collecting

didn’t yet have scientific names anyway, Wallace would just need to

know whether he had them yet or not.

He assigned a number to each of the species he collected in a particular place

and listed the numbers in his collecting

notebooks, sometimes with a few notes about the species—two of these

notebooks are in our museum here,

and one in the Linnean Society’s library.

E T

How would you describe Wallace’s

reliance on local knowledge of the

species he was collecting? In a way, he was completely out on his own, with

one or two books to guide him; so, did

he depend on knowledge from local inhabitants on the islands?

G B

I

would say that, truly, avifauna distinctions and major patterns are simply not

discernable to the average layperson in the archipelago. Wallace’s assistant, Ali,

was about as far from a scientist as one could get. So, understanding the newness

of a species is the result of knowledge of the descriptions themselves. There’s

a much more complicated relationship between the scientific descriptions and

the species collected than might first appear to certain historians of science.

Some tend to be rather politically correct these days and say that local assistants

deserve so much of the credit because they really understood the animals and

they are key in the whole process. John van Wyhe even says in his book Dispelling the Darkness that maybe

Wallace got his inspiration for the Wallace Line by staying at a local person’s

house on Lombok.1 In reality, the local

people really don’t have a clue about major biological patterns like that. So

no, it was only Wallace, with a very broad picture of the whole situation, who

would have seen the significance in species breaks and continuums across the

islands of the region. He knew that the cockatoo was centered in Australia and

that a few could be found in Lombok, but no further west. Who else would have

been able to draw that kind of conclusion?

Meanwhile, as

I said, Ali was completely illiterate. He had no scientific background, no

knowledge about the wider issues. It’s a bit like saying that Darwin’s gardener

deserves a share of the credit for Darwin’s great work on carnivorous plants

because the gardener helped to grow the plants. Ali went out and shot birds.

Most of the time, he didn’t know what the significance of the target was. Even

if he shot the first Wallace standardwing and thought it was new—and it would

have been new to him—it could have been discovered by somebody 100 years earlier.

It was Wallace who had the specialist knowledge, and that’s what counts—not

just collecting the stuff.

E T

Maybe this

leads us towards geography. What is the importance of Wallace’s work on the biogeographical

distribution of species?

G B

Well, rhinos

and tigers are on one side of the Wallace Line, while marsupials, cockatoos,

and birds-of-paradise are on the other. As Wallace said in one of his early

papers, when you look at two islands like New Guinea and Borneo, they seem very

similar. They are similar in their climate, and their forests look the same on

the face of things, and yet in Borneo you have monkeys and in New Guinea you

have tree kangaroos and marsupials, but no monkeys. This was Wallace’s key argument

against Charles Lyell’s idea regarding “centres of creation,” which held that

over geological time, as climates changed, God would create species fitted for

the new environment. For Lyell, if the climate changed from a desert to a rain

forest, then God would create a whole bunch of monkeys. But this theory

wouldn’t explain why everything to the west has monkeys and to the east there’s

marsupials. Same climate, east and west. So why would God create different organisms

to live in trees and eat leaves in such similar places? Why not just create

monkeys everywhere?

A S

Wallace

not only argued with Lyell over biogeographical distribution; he also envisioned

a mode of display for the museum that would show a continental evolutionary

panorama of the species. Did he also have a certain curatorial agenda, so to

speak?

G B

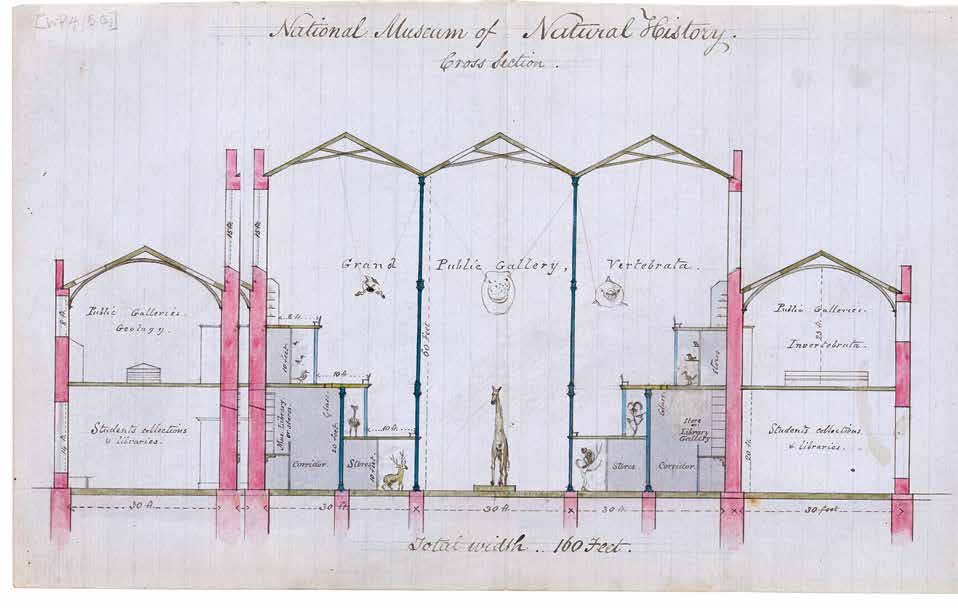

Well,

he did apply for a position as the director of the British Natural History

Museum, which was to be at Bethnal Green. The collection used to be at the

British Museum with all the archeology, but they wanted to make a new museum.

The curious thing is that Wallace sent Richard Owen drawings of how to arrange

the ideal collection of natural history, and the ideas in them are strikingly

similar to the way our museum is actually designed. You can almost imagine Owen

actually taking the ideas directly from Wallace. You have to look at the

drawings because they’re incredibly similar.

E T

Do you have

the original correspondence?

G B

No, I

don’t think so. This was before the museum was built. Wallace wrote a paper

about the design of natural history museums.2

He was the first to suggest that animals from one particular place or habitat

should all be displayed together in order to give a sense of the fauna in that

area. Museums like ours and the Powell-Cotton Museum, which still has the best

formal dioramas in Britain, obviously took up this idea. I think the American

Museum of Natural History has the best formal dioramas anywhere in the world. Unfortunately,

there are no formal dioramas in our museum anymore. There used to be some in

what’s known as the Rowland Ward Pavilion—Rowland Ward, the taxidermy company,

produced these dioramas free of charge for the museum with the agreement that

they would always be there on display. However, about 10 years ago or so, the

museum broke this agreement and destroyed them.

E T

Why? Aren’t

they of some historical value?

G B

They

were just too old-fashioned. The museum needed space for storing old wooden

cabinets and things. There was a beautiful display of a scene on the African

Plains with a giraffe and giant sable antelope and then one of the Congo

forests with other animals. It’s a shame they were destroyed. As for the formal

diorama idea, I don’t know if Wallace ever published another paper on it or

whether it was just present in his book The

Geographical Distribution of Animals. The plates sort of show the animals

of one place illustrated together.

A S

This brings me

to another question about curatorial thinking, about the importance of

commemorating Wallace. Why is it important for you to bring the memory of Wallace

into the grand narratives (especially of Darwin) already dominant in the space?

G B

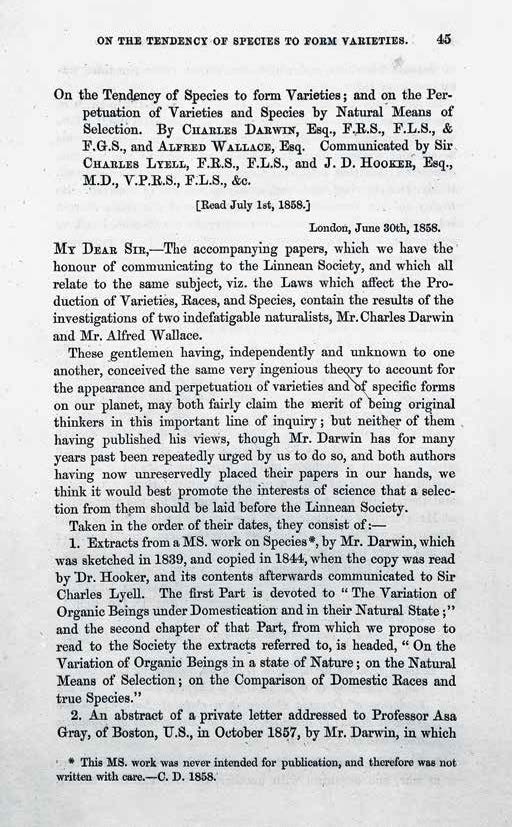

I

think the current story about the theory of natural selection is fatally flawed,

and is just a kind of fairytale. Darwin has been central while all the other

people have been forgotten. After all, Wallace was the co-discoverer of the

theory, as he published the paper with Darwin 14 or 15 months before On the Origin of Species was published.

So, in my view, he deserves half the credit, but not only that! He and Darwin

almost exclusively, together, laid the foundations of modern evolutionary

biology and all the other add-on theories in the early days, like understanding

animal colouration in an evolutionary context, biogeography, etc. You know, if

you think about the lasting scientific achievements of some of the prominent

biologists of the nineteenth century like Haeckel and Huxley, you can’t really

come up with anything. No major theoretical ideas that they developed have

lasted to this day, whereas both Wallace and Darwin made really major

contributions that still endure.

A S

So

there’s a concern for historical accuracy, but what about the elements of

stories that can be told differently through Wallace than Darwin. For example,

Wallace is sometimes called the father of conservationism. He was very

outspoken on certain issues which we’d now call conservation, which seem quite

relevant for contemporary purposes.

G B

Personally, I

think that Wallace’s role as an environmentalist has been a bit exaggerated. He

didn’t really write that much about it. And yet, what he did write was very

powerful and it was probably far ahead of its time. For people like Darwin, on

the other hand, it was wonderful that all the natural habitats were going to be

replaced by monocultures; he thought that was progress. Wallace sometimes

thought like that, but he realized that there would be a major loss of scholarship

if all these species were destroyed by development. He was also passionate

about the giant redwoods and their destruction in America. He met the pioneer

of American conservationism, John Muir, and Wallace was ahead of his time in

that respect, but he didn’t really focus his work on environmentalism or

conservationism. I suppose that back then it was far less of a problem; it

wasn’t nearly as serious as it is today.

A S

We are eager

to know whether the species Wallace collected could still be found today, or,

if one could currently come up with the theory of natural selection based on

available specimens, given the habitat loss one encounters in certain parts of

Indonesia?

G B

Actually,

very few of the species of insects and birds that Wallace collected in

Southeast Asia are known to be extinct. I can’t think of any, in fact. Many of

them are probably much more rare than they were, but if you had all the

official permissions you could still make collections like Wallace’s today. But

it would be impossible now to travel from island to island shooting every bird

you wanted. Anyway, collecting birds is not done very often these days. So, the

birds are still there, and you could go to Halmahera and kill a whole lot of

Wallace standardwings if you had permission. But that wouldn’t be a very responsible

thing to do given how rare they are. With insects, it’s a different picture

because, in general, you can’t collect enough of one particular species to

damage the population. At least it’s pretty difficult to do so. But entomologists

are still very active in Indonesia, observing habitats and collecting different

kinds of species, just like Wallace did.

E T

So,

even though larger mammals are extinct or rare, there’s still a wide array of

living evidence for natural selection?

G B

Sure,

it’s just that the political situation has changed. It would actually be

impossible today to just travel wherever you like and collect what you wanted. So,

say for example that the Wallace Line hadn’t yet been discovered. There are two

ways you could discover it today: either by doing all the collecting yourself, or

by reading enough about the patterns that others have discovered. You might be

able to work it out just by reading about the distributions of various groups.

E T

Are such

categories changing as a result of new forms of DNA analysis?

G B

Not as

much as you might think. It tends to be that DNA studies confirm what expert

taxonomists have always thought, or at least that’s the overriding trend. A

good example is some work that I did on cockroaches and termites; I initiated a

big DNA study of these critters, and we finally proved that termites are

actually, truly cockroaches that have evolved to be highly social. This was

actually first proposed in the 1930s using obscure morphological

characteristics like the structure of the gizzard and different protozoa in the

guts of termites and cockroaches—very technical, anatomical things. This is the

cockroach tree. [Fig. 06] Rather than being

an outlying relative, termites arise from within the tree. Since then, other DNA

and RNA studies have confirmed our findings. Anyway, all of this is to say that

we reinforced what expert morphologists realized a hundred years ago.

E T

What about

mimicry? This idea has been very important for discussions of natural

selection; have these discussions been changed by more recent DNA or RNA

studies?

G B

Well

no, actually. Colour patterning and mimicry were the first great tests of the

natural selection theory. If you look at the early papers on the topic, they

used this example because it was clear—one species has evolved to look like

another species because one’s tasty and one’s nasty, or whatever. All of the

arguments were centered around these visual examples, and mimicry was of great

interest. Wallace proposed a lot of the ideas that are still valid today about

animal colours and polymorphic mimicry in butterflies, where one species has

females that look like members of several different species living in the same

habitat. In the swallowtail butterfly, for example, males will all look the

same and they wouldn’t be mimetic, but the females have different morphs and

each of those discrete morphs mimics a different species of poisonous butterfly.

Wallace was the first person to explain this.

A S

Can

you explain the significance of this?

G B

Well,

there aren’t discrete morphological types of human. We’re mixtures of our

parents; whereas with butterflies, there’s one kind of male with, say, black

wings, and then five different female colour patterns, each of which has

evolved to look like a different species of poisonous butterfly. When they

breed, you always get the same males and this array of different female

patterns. That is what we call polymorphic mimicry. Wallace discovered this in

the Southeast Asian swallowtail butterfly, Papilio

memnon, but it became more famous when something similar was discovered in

a habitat of swallowtails called Papilio

daedalus in Africa. It was then studied for a hundred years and still, to

this day, researchers are trying to work out how the different mimetic morphs

actually arose, and the genetics of this process. Wallace must have gotten a

batch of eggs, reared the caterpillars, and saw that they produced black males

and five different types of females; he realized that all these females he

thought were different were actually of the same species.

A S

How does this

relate to sexual selection?

G B

Thinking

about the underlying purpose of animal colouration and display, the modern

theory of sexual selection actually has more to do with Wallace’s ideas than

Darwin’s. Everyone says that Darwin came up with the theory of sexual selection

and Wallace rejected it, but if they knew enough about the modern theory, it’s

actually quite the reverse!

A S

Can you parse

these two theories?

G B

Darwin’s

theory says that the females of a species have an appreciation of beauty and that

they pick the most beautiful males to mate with because they deemed them to be beautiful. Wallace couldn’t imagine that

a butterfly would have an aesthetic sense. Why would a tiny insect brain be

able to judge beauty in this way? He couldn’t understand how female butterflies

could choose more beautiful males, so he argued against Darwin’s idea, which

suggested in essence that these creatures knew what beauty was and chose it for

its own sake. Wallace’s idea was that the plumage, for example, had some other

function. It was basically the most vigorous males who were able to produce the

best plumage, which was a sign of vigor and health. So, by choosing the best

plumage the females were choosing the healthiest males. Or, in the case of

antelopes, say, it would be the males with the biggest horns who were chosen by

the females because they knew their offspring would have those characteristics.

That’s what the modern theory of sexual selection is all about, which follows

from Wallace’s “better genes” argument for selection, as opposed to the

aesthetic sense idea from Darwin. In sexual selection, for Wallace, beauty is

an index or register of health and vigor, not an aesthetic quality chosen for

its own sake.

A S

To conclude,

can you summarize what distinguishes Wallace from his contemporaries? Why is he

so special in the history of science?

G B

He was poor

and had no infrastructure. I think these things allowed him to develop a much

deeper understanding of nature because he was so closely engaged with and

attentive to the local culture and customs. When people they think of Wallace—if

they think of Wallace at all—they think of the Wallace Line, or maybe even the

co-discovery of natural selection, but his legacy goes far beyond that. His

contributions to biology are very important, much more so than most of the

other people in his day, such as T.H. Huxley or Charles Lyell, even. Only

Darwin made similar contributions.

A S

What about

Ernst Mayr?

G B

People will often

suggest that Ernst Mayr came up with the biological species concept, but he

actually took it from Wallace, who was the first to claim that species should

be defined as interbreeding groups that are

reproductively separate from other such groups. There’s nothing in On the Origin of Species that actually explains what a species is. So,

even though it’s a book about their origins, Darwin never defines what he means

by species.

Wallace’s

contributions to biology went far beyond co-discovering the theory of natural

selection, upon which the modern study of evolution is based.3 Unlike Darwin, he rejected Lamarckism. In fact,

he was the first natural scientist to reject it and was, in fact, the first

Neo-Darwinian. Wallace devised the first modern species concept, a slightly

modified version of what would later become known as the biological species

concept. Interestingly, although many people think of sexual selection as

Darwin’s theory, Wallace’s argument

about selection is regarded by many today as more plausible than Darwin’s

belief that mates are chosen based on aesthetic grounds, as I said earlier. The

Great American Interchange, when South America and North America connected via

Central America and the animals of the north moved down, and vice versa—that

was also Wallace’s idea. There were other things, too, like recognition marks

in animals; a scientific paper about colour patterns in monkeys recently reinvigorated

Wallace’s concept of recognition marks. He was also the founder of

astrobiology, he came up with the first plausible evolutionary idea of aging

and death, and he was first to propose mimicry in birds and polymorphism in

butterflies. There was also the Wallace Line, of course.

A S

Do you

think there is a way that the study of Wallace could contribute to the current

discussion of the Anthropocene?

G B

I

think we should call it the Destructoscene.

G B

I think we should call it the Destructoscene.

I think we should call it the Destructoscene.

1 John van Wyhe, Dispelling the Darkness: Voyage in the Malay Archipelago and the Discovery of Evolution by Wallace and Darwin (Singapore: Scientific World, 2013).

2 See Alfred Russel Wallace, “Museums for the People,” The Alfred Russel Wallace Page, http://people.wku.edu/charles.smith/wallace/S143.htm.

3 Charles H. Smith and George Beccaloni, eds., Natural Selection and Beyond: The Intellectual Legacy of Alfred Russel Wallace (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010).