Necroaesthetics: Denaturalising the Collection

Anna-Sophie Springer, Etienne Turpin

Published 21 June 2016

It is therefore an important object which governments and scientific institutions should immediately take steps to secure, that in all tropical countries colonised by Europeans the most perfect collections possible in every branch of natural history should be made and deposited in national museums, where they may be available for study and interpretation. Alfred Russel Wallace, “On the Physical Geography of the Malay Archipelago” (1863, p. 233)

And this is perhaps the crucial paradox that the Anthropocene brought to light: different regimes of power will produce different natures, for nature is not natural; it is the product of cultivation, and more frequently, of conflict. Paulo Tavares, “The Geological Imperative” (2013, p. 209–39)

A young visitor encounters a dead fox at the Oxford Natural History Museum, Oxford, UK, 2015. Photograph courtesy Etienne Turpin.

When visiting an ethnographic museum, especially in Europe, the presence of colonial history is unavoidable. The staging of cultural otherness, the black-and-white photographs of past expeditions, the accumulation of non-industrial artefacts, even the fashionable contemporary installations cleverly reflect on these histories, all serving to remind the visitor that the modern museum is a product of European colonialism. Historical ethnographic collections can't pretend that the objects on display were not embedded in scenarios of a certain liveliness before entering the museum. For example, a musical instrument in a vitrine conjures up questions about how it would have been played by someone in the past, and one often wonders about the events, or the violence, that brought it to its current state of exhibition. Even though contemporary ethnographic museums have been under significant pressure for decades to expose their colonial origins, and some have done so with partial success, encountering an ethnographic collection provokes an awkward sense of appraisal because the collection itself remains an index to colonial violence, which is difficult to conceal. How can it be apprehended aesthetically when it has almost certainly been obtained through coercion?

Yet, upon entering the beloved halls of a natural history museum, a strangely naturalised sensibility seems to neutralise the scenography. Among the necroaesthetic presentation of various arrays of taxidermy specimens – from rare turtles to soaring avifauna, from skeletal cetaceans to combative Arctic bears – one rarely feels any anxiety about their origins or the violence that rendered these once live beings into museological curiosities. In their reanimation as natural history collection objects, the specimens on view declare their neutrality, which makes it difficult to connect their presence to the political, colonial, or ecological sites of struggle from which they were extracted.

Birds in the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery, Hobart, Australia, 2013. Photograph courtesy of the authors.

What we want to stress here is that all collections – whether they are ethnographic or natural, artistic or cultural – are comprised of things that have been collected. By being rendered collectable, each specimen or artefact has been produced as an object indexing a scientific will to knowledge. This will to knowledge is epistemological as much as it is institutional: it is a form of normalised violence that must be accounted for within the contemporary practice that seeks to both decolonise and ecologise the museum – two moves that we consider as entirely necessary. 1 In these fantastic inheritances called natural history collections, is it possible to denaturalise the act of “collecting” to renegotiate the co-production of knowledge – past, present, and future? In order to enable this to occur, it is necessary first to decipher the contemporary necroaesthetic strategies, which perpetuate the naturalised fiction of specimen collections.

In the Oxford Natural History Museum, we recently encountered an elegantly stuffed deer placed near the entrance of the main exhibition hall. A sign beside this formidable specimen invited visitors to pet the fur of this now inanimate object. Many viewers seemed indeed to have great fun doing this. “Exhibition was a practice to produce permanence, to arrest decay”, writes Donna Haraway in her essay on museum taxidermy (1989, p. 55). Focusing on the late nineteenth-century genesis of the American Museum of Natural History, Haraway unpacks how the naturalisation of certain civil hierarchies (i.e. human exceptionalism and patriarchy) underlies the presentation of organic hierarchies constructed by means of inanimate taxidermy. “The animal is frozen in a moment of supreme life, and man is transfixed. No merely living organism could accomplish this act. [...] This is a spiritual vision made possible only by their death and literal re-presentation. Only then could the essence of life be present. Only then could the hygiene of nature cure the sick vision of civilized man. Taxidermy fulfills the fatal desire to represent, to be whole; it is a politics of reproduction” (Haraway 1989, p. 30). To this day, natural history dioramas tend to compose three-dimensional tableaus of wild nature, while anthropogenic visions of urbanisation, deforestation, mining, extinction, or pollution remain an absolute exception. So what could possibly be the point of an invitation to tenderly caress a stuffed deer – a specimen so dead that it is not even indifferent to our touch – other than to naturalise the obvious, disturbing sense of death signalled by the eerie stillness of these once live creatures? While standing in a hall filled with dead creatures made to look animate or frozen in space-time, an invitation to pet the collection surely encourages visitors to suspend disbelief, in favour of the wish-image that this collection is somehow, against all empirical evidence, natural.

Bones in the courtyard of Het Natuurhistorisch Museum Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2015. Photograph courtesy of the authors.

While most other museums haven't yet started encouraging visitors to pet the specimens, countless other examples show specimens in partial stages of reanimation. The natural history section of the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery in Hobart, Australia, for instance, discloses the steps of preserving ornithological specimens in a vitrine presenting birds in various stages of preparation. A less classical strategy was devised by Kees Moelicker, Director at the Rotterdam Natuurhistorisch Museum, where windows onto an inner courtyard reveal the curious sight of animal skeletons recklessly strewn about as if they were leftovers from some ruthless carnivorous feast. Partly decayed and covered in a layer of green moss, these unwanted bones of deceased zoo animals are more living than the toxified taxidermy animals simulating aliveness in the interior galleries. At first glance, one might expect that such revelations would undermine the “reality effect” of their correlative reanimated objects, but surprisingly the opposite is the case – the completed, glassy-eyed reconstructions become even more convincing through this necroaesthetic sequencing. 2

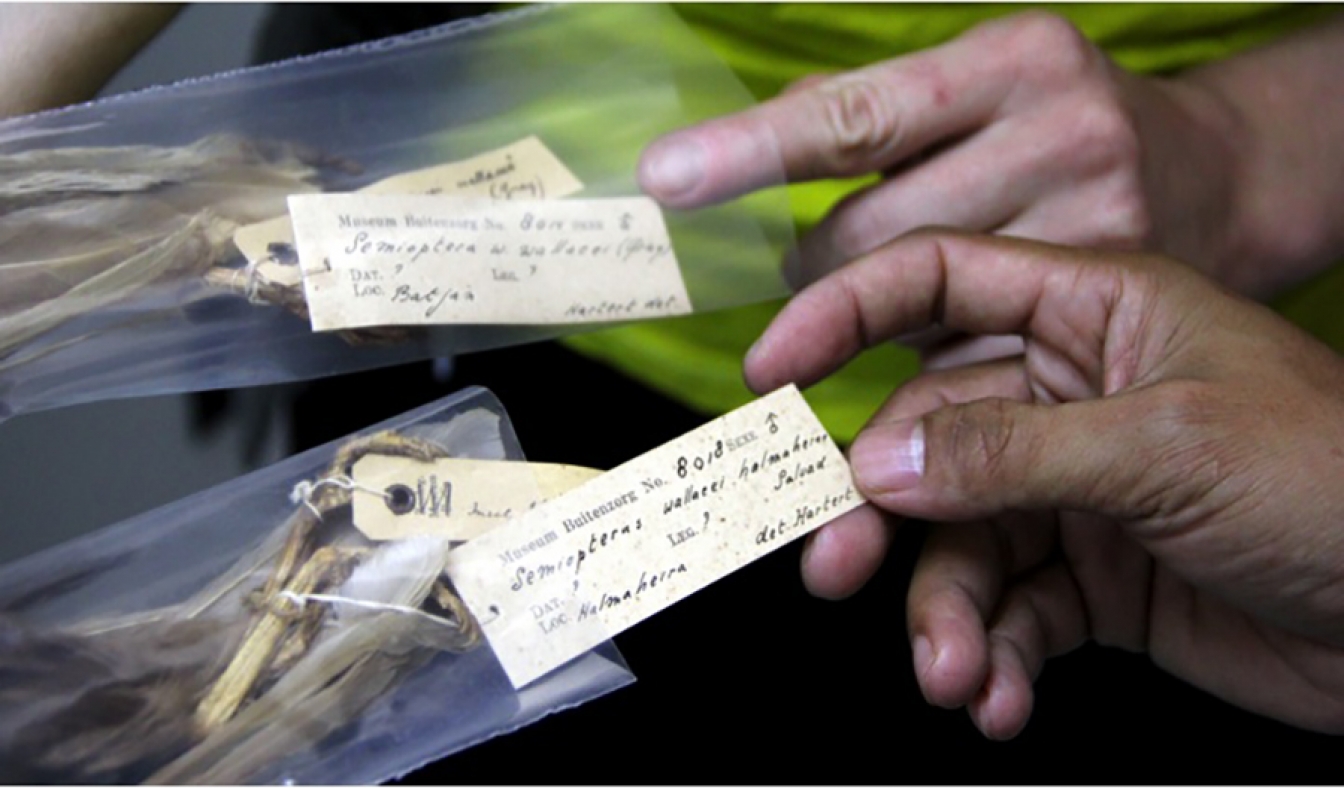

Semioptera wallacei specimens in the ornithological collection of the Indonesian Institute of Science, Cibinong, Indonesia, 2015. Photograph courtesy of the authors.

According to Jonathan Crary, taxidermy is “continuous with the operation of both cinematic and photographic illusion” (Crary 2014, p. 163, p. 165). It is not, he says, a “nature morte but a glimpse of timelessness in the present. The objects are not a symbolic form of survival in the face of time's destructiveness, but an apprehension of the marvelous, of a real that is outside of a life/death or waking/dream duality”. We call this experience of viewing viviscopic in order to emphasise the ways in which the observer can be trained by the necroaesthetic procession of natural history collections to see as alive what is evidently, even at times emphatically, dead.

125,660 Specimens of Natural History (detail of Table 19, including bird specimens described in scientific papers by Alfred Russel Wallace), Jakarta, Indonesia, 2015. Photograph courtesy of the authors.

As scientists are now essentially in agreement that the last 400 years of human impact have pushed the Earth into a crisis called the Sixth Mass Extinction, the question of life and death takes on new meaning with troubling urgency. The Dodo is considered to be the first animal to have been exterminated as a consequence of European colonialism in Madagascar in the sixteenth century (Grove 1996, p. 145 and following); yet, since 1900, close to 500 vertebrate species have become extinct. According to a study by the World Wildlife Fund, the number of wild animals has halved in the last forty years alone. This is tragic news for beloved species such as elephants, rhinoceros, orangutans, and tigers, but it is no less violent for less admired animals such as vultures and dung beetles. Since a diminished evolutionary gene pool can be detrimental for surviving epidemics, the American evolutionary biologist and conservationist E.O. Wilson has urged that half of the Earth should be abandoned by humans to allow for the regeneration of non-human biodiversity. Even if Wilson's claim must be read as a provocation rather than a feasible solution, in the context of exacerbated and irreversible destruction of habitat around the world, especially in hotspots of tropical biodiversity, we decided to consider zoological specimen collections as evidence of the “slow violence” of the Anthropocene (Nixon 2011).

125,660 Specimens of Natural History (detail of Table 19, including bird specimens described in scientific papers by Alfred Russel Wallace), Jakarta, Indonesia, 2015. Photograph courtesy of the authors.

In a recent project, 125,660 Specimens 3, we attempted to raise questions about collecting and environmental violence by investigating a single natural history collection, perhaps the largest one ever assembled by any naturalist. Alfred Russel Wallace collected 125,660 specimens for European institutions and elites during his expedition in Nusantara, the Indonesian archipelago, from 1854 to 1862. One of the first things we learnt was the organisational logic that distinguishes ethnographic and zoological collections: in the latter, specimens are recorded in existing taxonomic orders rather than stored according to their collector. Still, field biologists studying Wallace's legacy soon emphasised the underestimated singularity of this fantastic aggregation. A younger contemporary of Charles Darwin, Wallace played an important role in the formulation and publication of the theory of evolution by natural selection in the 1860s. Although he was primarily a commercial specimen collector, rather than a scientist working for the academy, it was on the basis of his own gigantic collection that Wallace managed to draw groundbreaking conclusions about the origin of species hastily co-published with Darwin in 1859. Wallace's Malay collection is both the material evidence for a revolutionary scientific theory and the point of departure for the modern natural history museum as we know it – an institution whose early mission was to popularise the idea of evolution, and therefore of human exceptionalism, in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries (Asma 2001).

125,660 Specimens of Natural History (facing entrance), Jakarta, Indonesia, 2015. Photograph courtesy of Komunitas Salihara.

When Wallace travelled the region, he was exposed to “more than ten thousand species of trees, about a tenth of the world's flowering plant species, about an eighth of all mammal species, nearly a sixth of all reptile and amphibian species, a sixth of all bird species, and about a third of all fish species” (Daws & Fujita 1995, p. 185). Today, as the world's largest exporter of crude palm oil, Indonesia is witnessing the rapid disappearance of its rainforests, which is forcing the region's biodiversity into a highly stressful condition. Many of the zoologists we interviewed during the exhibition research doubted that it would be possible to develop a theory of evolution today because of the extremely degraded condition of the environment.

Bird of Paradise in the ornithological collection of the Indonesian Institute of Science, Cibinong, Indonesia, 2015. Photograph courtesy of the authors.

Disturbed by the discrepancy between the preserved Wallace specimens in Europe and their devastated place of origin, we established a curatorial partnership with the Museum Zoologicum Bogoriense (MZB), the Indonesian Institute of Science, and the contemporary art gallery Komunitas Salihara in Jakarta. In cooperation with the Schering Stiftung in Berlin, and with the additional funding from the Goethe-Institut, the Norwegian Office for Contemporary Art, and the British Council, we were able to commission thirteen artists from Indonesia to create new projects in close exchange with MZB's scientific curators. The exhibition 125,660 Specimens of Natural History aimed to bring this colonial legacy to the forefront of contemporary discussions regarding Indonesian forest conservation, while also raising questions about land use and the protection of biodiversity through oblique strategies, artists' interventions, and repeated provocative adjacencies.

Installation view of A Taxonomy of Palm Oil: U.S. Edition, in the exhibition Emergent Ecologies, curated by Eben Kirksey, Butler College, Princeton University, 2016. Mixed-media installation by the authors, including 100 samples of American commercial products that contain palm oil or a derivative of palm oil.

In the context of natural history collections, ecologising the museum means accounting for and negotiating with the various violent modes through which “collecting” took place. Such a disposition would necessarily denaturalise the collection and its viviscopic specimens, which vie for visitors' imaginations and investments. It would question the necroaesthetic experience on offer in these institutions and encourage denaturalising the tendency to neutralise the feelings of irretrievable loss and anxiety that accompany any visit. Petting the specimens might not be the most relevant comportment in this creaturely columbarium when we accept the reality that an anthropogenically-effectuated mass extinction is in full effect outside. Rather than helping bury these feelings of loss, the future of the natural history museum, and of “ecologising museums” more broadly, might mean instead the production of exhibitions and programmes that allow visitors to confront the sense of despair that such a violent reality occasions.

Even while acting as its instrument, Wallace was no stranger to the experience of melancholy brought on when considering the violence of the will to science. An awkward estimation of his privileged human, masculine, and colonial techniques of observation stumbles over the recognition of imminent consequences. The passage is remarkable and worth quoting in its entirety:

“I thought of the long ages of the past, during which the successive generations of this little creature had run their course – year by year being born, and living and dying amid these dark and gloomy woods with no intelligent eye to gaze upon their loveliness; to all appearance such a wanton waste of beauty. Such ideas excite a feeling of melancholy. It seems sad that on the one hand such exquisite creatures should live out their lives and exhibit their charms only in these wild, inhospitable regions, doomed for ages yet to come to hopeless barbarism; while on the other hand, should civilized man ever reach these distant lands, and bring moral, intellectual and physical light into the recesses of these virgin forests, we may be sure that he will so disturb the nicely-balanced relations of organic and inorganic nature as to cause the disappearance, and finally the extinction, of these very beings whose wonderful structure and beauty he alone is fitted to appreciate and enjoy.” (Wallace 1869)

Taxidermy specimen perched on an air conditioning unit in the ornithological collection room of the Indonesian Institute of Science, Cibinong, Indonesia, 2015. Photograph courtesy of the authors.

Is this not the very melancholy that viviscopic presentations of specimens are meant to neutralise? Surely, even for an unconscious few milliseconds upon entering the main hall of a natural history museum, the contemporary visitor connects the strange and ruthless affect of seeing nature destroyed with the reality of seeing nature this way? Given this comportment, perhaps it is not the explicit colonial sentiment of Wallace's remarks that should be the most startling, but their cutting contemporaneity. It is this melancholic paroxysm that is characteristic of a troubling moment of recognition, that is, when we reach out to pet the specimen to calm an anxious excitation having noticed something deeply disturbing about this celebrated view on, and of, death and capture. How, then, to inherit this scene otherwise? Ecologising the museum means deciphering the necroaesthetic sensorium of natural history to renegotiate the terms of inheritance and inhabitation on this damaged Earth.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Vincent Normand, Tristan Garcia, Filipa Ramos, Lucile Dupraz, and Etienne Chambaud for their generous friendship and careful engagement while thinking through the question of necroaesthetics during the writing of this essay.

References

Asma, S. 2001, Stuffed Animals and Pickled Heads: The Culture and Evolution of Natural History Museums, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Carrington, D. 2014, "Earth has lost half of its wildlife in the past 40 years, says WWF", The Guardian, 30 September.

Crary, J. 2014, 24/7: Late Capitalism and the End of Sleep, Verso, London.

Daws G. & Fujita, M. 1995, Archipelago: The Islands of Indonesia – From the Nineteenth-Century Discoveries of Alfred Russel Wallace to the Fate of the Forests and Reefs in the Twenty-First Century, University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles.

Grove, R. 1996, Green Imperialism: Colonial Expansion, Tropical Island Edens and the Origins of Environmentalism, 1600–1860, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Haraway, D. 1989, "Teddy Bear Patriarchy in the Garden of Eden, New York City, 1908–1936", Primate Visions: Gender, Race, and Nature in the World of Modern Science, Routledge, London.

Nixon, R. 2011, Slow Violence & the Environmentalism of the Poor, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass.

Tavares P. 2013, "The Geological Imperative: On the Political Ecology of Amazonia's Deep History", in E. Turpin (ed.), Architecture in the Anthropocene, Open Humanities Press, London. Open access: https://archive.org/details/Turpin-2014-Architecture-in-the-Anthropocene.

Wallace, A.R. 1863, "On the Physical Geography of the Malay Archipelago", Journal of the Royal Geographical Society, vol. 33, 1863.

Wallace, A.R. 1869, The Malay Archipelago, Harper & Bros, New York.

Wilson, E.O. 2006, "Half-Earth", Aeon, London, Melbourne, New York.

Asma, S. 2001, Stuffed Animals and Pickled Heads: The Culture and Evolution of Natural History Museums, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Carrington, D. 2014, "Earth has lost half of its wildlife in the past 40 years, says WWF", The Guardian, 30 September.

Crary, J. 2014, 24/7: Late Capitalism and the End of Sleep, Verso, London.

Daws G. & Fujita, M. 1995, Archipelago: The Islands of Indonesia – From the Nineteenth-Century Discoveries of Alfred Russel Wallace to the Fate of the Forests and Reefs in the Twenty-First Century, University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles.

Grove, R. 1996, Green Imperialism: Colonial Expansion, Tropical Island Edens and the Origins of Environmentalism, 1600–1860, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Haraway, D. 1989, "Teddy Bear Patriarchy in the Garden of Eden, New York City, 1908–1936", Primate Visions: Gender, Race, and Nature in the World of Modern Science, Routledge, London.

Nixon, R. 2011, Slow Violence & the Environmentalism of the Poor, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass.

Tavares P. 2013, "The Geological Imperative: On the Political Ecology of Amazonia's Deep History", in E. Turpin (ed.), Architecture in the Anthropocene, Open Humanities Press, London. Open access: https://archive.org/details/Turpin-2014-Architecture-in-the-Anthropocene.

Wallace, A.R. 1863, "On the Physical Geography of the Malay Archipelago", Journal of the Royal Geographical Society, vol. 33, 1863.

Wallace, A.R. 1869, The Malay Archipelago, Harper & Bros, New York.

Wilson, E.O. 2006, "Half-Earth", Aeon, London, Melbourne, New York.