Worlds After Wallace

George Beccaloni ( G B )

in conversation with Anna-Sophie Springer ( A S )

& Etienne Turpin ( E T )

Among the experts on Alfred Russel Wallace in the English-speaking world, Dr. George Beccaloni—a former curator of entomology at London’s Natural History Museum, and the Director of the Alfred Russel Wallace Correspondence Project—is perhaps the most compelling advocate for a reassessment of Wallace’s place in the history of science. His knowledge and excitement are contagious, and throughout our various visits, tours, and conversations, we became increasingly certain that our curatorial engagement with the legacy of Wallace was a necessary project to see through, despite numerous obstacles. During our research, we met with George in his office, while tending to the museum’s insect collection, at his home, and in Epping Forest (one of England’s oldest), to discuss the significance of Wallace’s collections and the legacy of his work today. What follows is an edited version of these various conversations, organized thematically (instead of chronologically) for readability. We are grateful to George for his generosity, mentorship, and good humor over the years. He has helped us grasp the nuances of Wallace’s thought, the importance of natural selection, and the amazing world of entomology.

A S

Given your expertise, it would be great if you would start off by providing a bit

of context about Alfred Russel Wallace, The Malay Archipelago, and insect

collecting. I would also be particularly interested in how, at the point when the

theory of evolution was formulated, this transformation of knowledge changed

the way that museums were ordered.

G B

One of the predecessors of Enlightenment museum collections were the

Renaissance cabinets of curiosities, which were just assemblages of interesting and strange objects. After

the theory of natural selection was published and people started to accept that species had evolved from other

species, displays became much more

evolution-based. Wallace, as the co-discoverer of evolution by natural

selection, was partly responsible for this. As the founder of evolutionary

biogeography, Wallace was also responsible for another popular type

of display, the faunal diorama, where animals of a particular region are

shown together in one scene. All the taxidermy mammals of the Andes or

the Himalayas, say, are placed together against a natural background showing

some of the habitat. This method of display derives from the plates in

his important book, The Geographical Distribution of Animals. [Fig. 03.]

A S

Let’s step back a bit: who was Wallace and where did he come from?

G B

The basic story is very well known. Wallace was born to a downwardly mobile, middle-class couple in Usk, England (now part of Wales) in 1823. He was educated in Hertford, to the north of London, and had to leave school when he was only fourteen. Charles Darwin left school much later, when he was sixteen, and then went on to two universities. After leaving school Wallace educated himself from books and also attended working men’s clubs. He became interested in natural history whilst working with his brother as a trainee land surveyor, travelling in the countryside of southern England and Wales. His first interest was botany, as he wanted to identify the plants he saw whilst out surveying. He bought his first books on the subject and realized that there was a whole science behind the classification of plants and animals. He formed a collection of pressed plants in order to remember which species he had seen before and more accurately identify them from the books that he read. He then got a job for a year as a teacher in Leicester. That’s when he met Henry Walter Bates, a keen beetle collector who got Wallace passionate about insects. Wallace then returned to Wales and started collecting beetles, moths, and butterflies.

Fig. 01. George Beccaloni showing some of the beetles Wallace collected in Nusantara

to Anna-Sophie Springer in the storage of the London Natural History Museum. Photo by Etienne Turpin.

E T

Was entomology a fairly common

practice

at the time?

G B

Yes, there were many entomologists at the time, and they published their

records and observations in various

specialist journals, just as they do today. However, entomologists formed a

tiny proportion of the population, then as now. Most people think you’re

weird when you tell them you collect beetles, and probably the same was

true back then.

E T

Do you know how long this amateur

scientific community of entomologists was working before Wallace’s time?

G B

The number of amateurs studying

insects increased steadily from the mid-eighteenth century, and as a result

the insects and other fauna of Britain were pretty well known by the time

Wallace began collecting. By the 1850s natural history had also become very

popular among the general public. A friend of mine, the writer and artist Errol Fuller, who is interested in the history

of taxidermy, has said that everyone had to have a stuffed bird in their living

room at that time. So, there was a greater appreciation of and interest in

natural history, and a huge demand for showy foreign specimens to display

domestically—butterflies on the wall, or a stuffed bird. However, Wallace’s

market—the people who did serious scientific work on the collections he

sent back from his expedition through the Malay Archipelago (1854–62)—was

really just a handful of people. There were probably more amateurs doing

the serious work of describing species in Britain than there are now, but that’s

not the case everywhere. In Eastern Europe, for example, there are still many

amateurs doing that sort of work.

A S

Did the majority of specimens that

Wallace sent to Europe from the Archipelago end up in private

or public collections?

G B

Probably less than fifty percent were purchased directly by the British

Museum. Wallace mostly collected insect and bird specimens, and he

shipped them to his agent, Samuel

Stevens, in London. Stevens

had rooms near the old British Museum (the natural history collections that we have here in South Kensington used

to be in Bloomsbury, in what’s now the British Museum). When new shipments

came in, Stevens would let the scientists in the museum know, and

they would come to pick out all the things they thought were interesting or new. The rest of the material was then

sold to keen amateurs such as William

Wilson Saunders. Saunders would

take all of Wallace’s smaller orders of insects, whereas the beetles went

to certain specialists on the different

groups. For instance, Francis P. Pascoe got the longhorn beetles. Stevens

often kept some specimens aside for a certain collector. Then there was

the general public, who had very little

knowledge of natural history but wanted really showy specimens—

brightly colored parrots or hummingbirds or whatever—to decorate

their

homes. We don’t know what proportion

of specimens went to the third group of people because typically the

original labels were removed. Even if you went through collections

of old Victorian taxidermy today (and

there are many such collections), you wouldn’t know if they were Wallace

specimens or if they were collected

by someone else.

E T

But there was a certain accounting

procedure, was there not? Everything had to pass through Stevens,

who would have had some form of

master list to track payments owed to Wallace, no?

G B

Wallace kept rough records of how

many specimens and species he collected on each island and shipped

back to Stevens. His notebook

detailing his consignments to Stevens is in the Linnean Society library.

Unfortunately, however, Stevens’s

records do not survive.

A S

Are there any shipping papers

or transportation documentations

available?

G B

None that were issued by the actual

shipping agents, at least none that anybody has ever found. Maybe

Stevens had lists but they don’t

survive at all, so we only have fragmentary information, and we don’t even

know exactly where most of Wallace’s specimens are now. We have a fairly

good idea which museums have Wallace specimens in their collections,

but we generally don’t have lists of the specimens they have. Although I’m pretty sure that there must be

thousands of Wallace specimens in the Paris museum, there’s no list of them

and no way of easily finding them. This is also true in the Natural History

Museum, because our specimens haven’t been individually databased,

and won’t be for a very long time, if ever—the collection is just too huge!

We have about 25,000,000 insect specimens; although we don’t have a record of what Wallace specimens

we have, I have estimated that we must have roughly seventy percent of

everything he collected. Our museum not only purchased Wallace’s specimens

directly from Stevens, but many others came in collections formed by entomologists which were purchased,

donated, or bequeathed to the Museum when the collectors died.

The Oxford Museum of Natural History has the second biggest collection of

Wallace’s specimens, mostly insects. Sadly, in the whole of the Malay Archipelago there are only two Wallace

specimens—a dung beetle in the Sarawak Museum in Malaysia and

a drab little bird in the natural history museum in Singapore.

A S

So what first made you interested

in Wallace?

G B

When I was doing my Ph.D. on the evolution of mimicry in butterflies from

South America, I became interested in theories of animal coloration—for

warnings, camouflage, sexual selection, and so on. I realized that it was Wallace who proposed the majority of these

theories. I hadn’t really heard of him before, nor did I know that he was the

co-discoverer of natural selection, so I started to read a bit more about him.

I was reading James Marchant’s Alfred Russel Wallace: Letters and Reminiscences,

which says that Wallace was buried in Broadstone, Dorset, on a windswept hill. On the first outing that

I had with my wife-to-be, we happened to be camping in that area of Dorset

and I had just read this, so we ended up going to find Wallace’s grave.

After some searching, we eventually discovered it behind a huge conifer;

it was marked by a strange monument, which looks a bit like a phallus on a

stone base. I decided to find out who owned

it because I felt it was a shame that it was in such bad condition—you had to

climb inside the tree in order to see the name plaque, and the roots were

tipping it over. I contacted the cemetery

and they said that Wallace’s grandsons still owned the grave—I hadn’t realized

that any of his grandsons were still

alive. I managed to find the address of

his grandson Richard and wrote to him, saying that I’d seen their grandfather’s

grave was in a sorry state. He wrote

back saying something like, “Yes, it’s a

great shame. We do our best, but we’re

72 73 getting kind of old and we go there once

a year to clear shrubs and brambles

from the base.” As Wallace is one of the

greatest figures in the natural sciences, at least in biology, I decided that his

grave should be restored. I started the

Wallace Memorial Fund in order to raise

the money to do this and extend the lease on the plot. I’d discovered that the

lease only had another fourteen years to

run, after which time they would use

the plot for another burial and dispose of the monument.

I sent articles to various places

telling them about the fund and that I

was looking for donors. Within a pretty short time we had over 100 donors from

all around the world, which enabled

us to restore the monument, cut down

the tree that was pushing it over, put up a new bronze plaque explaining who

Wallace

was, and extend the lease

on the plot. By this stage I was in touch

with various people in places where Wallace had lived and they were really

interested in participating; working

with them, we set up other monuments.

A S

Tell us more about how Wallace collected

and identified his 125,660 specimens?

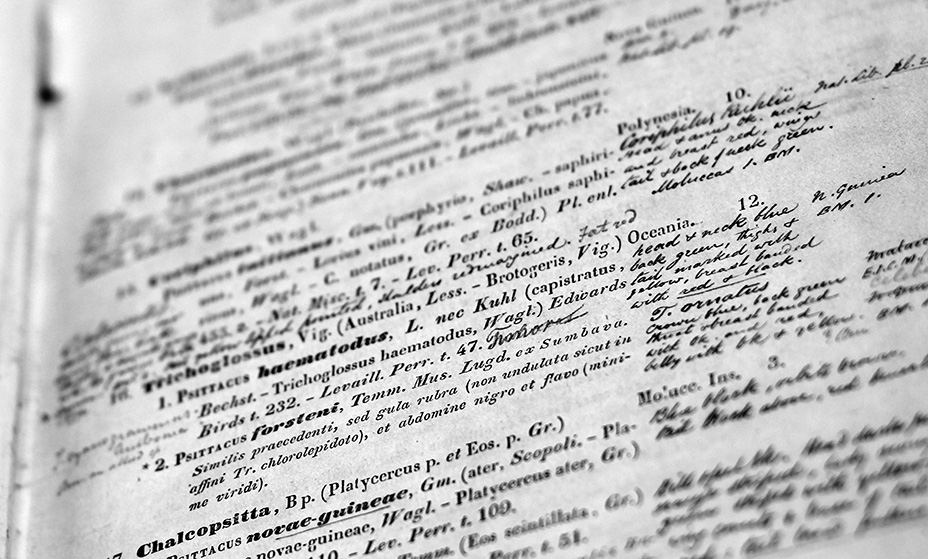

Fig. 02. A page from Wallace’s copy of Bonaparte’s Conspectus. Courtesy of the Linnean

Society London. Photo by Etienne Turpin.