The Museum as Archipelago

Anna-Sophie Springer

Published

I imagine the museum as an archipelago.

—Édouard Glissant

In 1948, the geography department at Harvard University was shut down for being “hopelessly amorphous” and for failing to produce “a clear definition of the subject” or to “determine its boundaries with other disciplines.” 1 This essay emerges from a much newer discipline, one that, in contrast to geography, has only just begun to exist as a proper academic field, but that is nevertheless enjoy ing its precocious status and attracting increasing theoretical inter est. Within the upstart discipline of “Curatorial Studies,” curatorial practice departs from the idea that curating historically entails car ing for artifacts within the institution, enabling the current dis course to turn its attention toward investigating and contouring forms of creative and critical agency, thus resulting in the production of knowledge with a performative element that has been called “the curatorial.” Like geography’s struggle for a convincing self-defini tion in the 1940s, curatorial practice today struggles with its own fluid boundaries. This fluidity, however, is the field’s strength; in what follows, I argue that far from being conceived of as a weakness, the openness of contemporary curatorial practice finds a retroactive and productive affirmation in the geographic and spatial theories that distinguish between settler and indigenous cartographies. 2

Machining Knowledge

The island was spread out under their eyes

like a map, and they had only to give names

to all its angles and points.

—Jules Verne

Most fundamentally, a map is an eidetic—visual, but also mental—representation

of an area. Such a form of representation is connected to an activity of production,

including navigational devices and models of surroundings, that is nearly as old as recorded history. 3 But maps, whether we

look at Roman, Greek, Chinese, or early European explorers, have also been important “weapons of imperialism” 4 and “tools for projecting power-knowledge,” 5enabling and expanding the scope and violence of countless colonial endeavours.

In fact, it was during the colonial scramble of the nineteenth century that “a pen across a map could determine the lives and deaths

of millions of people.” 6 In this instance, the map both anticipated and actualized

processes of human cultural intervention, rendering them conceivable and actionable. Despite this material actualization, however, it is important to stress that maps

are, in a large part, fictions of factual conditions; as human-made interpretations of the world, they foreground certain elements while leaving out others. What this means is that a map is not simply a mirror

image of the world but a creation with “semantic, symbolic and instrumental” content. 7 Therefore, maps do not represent anything;

instead, they produce effects by organizing knowledge and constructing perspectives. They are performative tools that can both frame and undo territories; read optimistically, every map has the potential to produce a new and different world.

One such example is R. Buckminster Fuller’s “Dymaxion Map” of 1943. While

our common Mercator projection privileges Europe and North America through orientation and distortion, Fuller’s projection unfolds the earth into a poly-directional

icosahedron, depicting the seven continents as a chain of islands (“one island

earth”) and the oceans as a connected,

fluid mass. The triangles of the map can be rotated towards each other in differ

ent ways, each time offering a radically different but always valid configuration,

making the Dymaxion Map a rare specimen of a world map that does not depend

on a predetermined perspectival centre. 8

Koryak Dancing Coat made of reindeer skin. The bleached disks symbolize the stars and constellations of seasonal skies, the waistband

the summer Milky Way. Image from David Woodward and G. Malcolm

Lewis, eds., Cartography in the Traditional African, American, Arctic,

Australian, and Pacific Societies, Vol. 2, Book 3, (Chicago: University

of Chicago Press, 1998): Plate 14.

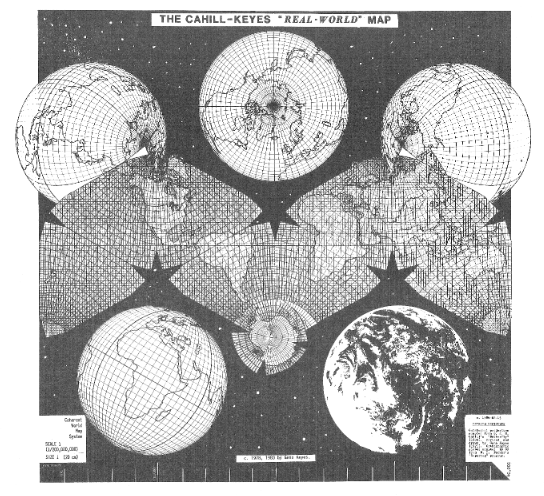

Draft version of Cahill-Keyes “Real-World” Map, 1984. Actual scale of original digital image is 1/100 million. This map is adapted from B.J.S. Cahill’s octahedral “Butterfly” projection, published in 1909. The graticule was newly devised, computed, and drawn by Gene Keyes in 1975, along with the coastlines, boundaries, and overall map design. Image courtesy of Gene Keyes.