On Natural History, Necroaesthetics, and Humiliation

Anna-Sophie Springer

Published

Behind the Wall

A man sets himself the task of portraying the world. Over the years he fills a given surface with images of provinces and kingdoms, mountains, bays, ships, islands, fish, rooms, instruments, heavenly bodies, horses, and people. Shortly before he dies he discovers that this patient labyrinth of lines is a drawing of his own face.

—Jorge Luis Borges, epilogue to “The Maker” 1

Since 2013, we have been working intensely on an itinerant exhibition cycle, “Verschwindende Vermachtnisse: Die Welt als Wald,” [”Disappearing Legacies: The World as Forest”], which after nearly three years of archival and field research, was presented consecutively at three German natural history museums, taking on the form of a traveling, free-to-the-public “art-science” exhibition about the legacy of the nineteenth-century naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace. 2 “Disappearing Legacies” was framed by two of the major collecting expeditions undertaken by Wallace, a younger contemporary of Charles Darwin, and his codiscoverer of the theory of evolution by natural selection. Wallace traveled to the Brazilian Amazon and Rio Negro from 1848 to 1852, and later to the Malay Archipelago between 1854 to 1862; he recorded many of his experiences in his best-selling book The Malay Archipelago: The Land of the Orang-utan and the Bird of Paradise-A Narrative of Travel, with Sketches of Man and Nature, first published after his return to London in 1869. As in his other publications Palm Trees of the Amazon and Their Uses, and Travels on the Amazon and Rio Negro, his meticulous description of natural sites and their flora, fauna, and geomorphy enables an exceptionally fine-grained comparison with current conditions, some fifteen decades lacer. When paired with artistic intelligence and curatorial interpretation, such comparative analyses reveal the speed and scale of environmental transformation in the torrid zone. Another significant aspect of Wallace's work is the idealized illustrations of tropical nature that he sketched and then commissioned for his books, and which, in turn, inspired some of the first habitat dioramas bringing together animals and plants of a biogeographical region in three-dimensional taxidermy tableaus. 3 His role as a colonial collector and, at least to some, an early environmentalist, also made Wallace a compelling conceptual persona for an exhibition about environmental crises because be allowed us to appropriate and displace the tradition of the biographical “great-man-of-science” retrospective through interventions that connected colonial history, contemporary environmental struggles, and the scientific will to knowledge into a close constellation of concerns that could nevertheless avoid the pitfalls of didacticism and overdetermination

of the work. 4

Borrowing the formal tropes of this exhibition format, the project could go on to consider how colonial archives of nature can be mobilized, disassembled, framed, and read in ways that enable a discussion of urgent ecological and systemic questions of injustice today. We were able to invite more than eighteen international artists and activists, commission eight new installations, and work with scientific curators and scholars to select specimens, artifacts, and other archival materials pertaining co the respective institutions and their geographies. 5 Time-and object-based installations by invited artists addressed urgent contemporary issues in Brazil and Southeast Asia; these artworks were exhibited alongside a series of curatorial assemblages developed through our collections research, all of which intervened in the natural history museum displays and their respective scenographies. Overall, this constellation of exhibition components constructed a dense and multilayered array of themes, images, stories, and sounds connecting the past and the present in ever-sh if ting refractions. In this way, the exhibition celebrated both diversity and biodiversity, by challenging aesthetic and agricultural monoculcures and by interrogating the modern colonial legacies that perpetuate epistemicide

and ecocide. 6 After years of research and on-site exhibitionmaking, we were relieved when the project came to an end in December 2018. Yet, while deinstalling the final version of the exhibition in the remarkable Zentralmagazin Naturwissenschaftlicher Sammlungen of Martin-Luther-Universitat Halle-Wittenberg, we noticed something completely unexpected that challenged the narrative of the exhibition. During this exhibition cycle we had repeatedly described the natural history museum as a kind of “secular church” that was, following the publication of the DarwinWallace Paper on natural selection in 1858, committed to promoting the theory of evolution as a heuristic for the appreciation of nature as such. Yet, upon closer inspection while we loaded our remal trucks, we noticed that the actual church that flanked the Halle Natural History Museum and presenting by contrast a more upright architectural posture, shared an architectural element with the museum—a single, contiguous buttressed wall connecting the two while also forming a part of the building of each institution and creating a courtyard between them. It may appear as a rather prosaic observation, but this banal architectural feature created a sort of conceptual shock as we pondered just what was protected in this common courtyard. This interruption of the calm of these final moments of the exhibition cycle suggested the need for further reflection regarding both our curatorial intervention and the institutional paradigm we meant to disrupt.

In what follows, we reflect on the concepts of necroaesthetics and humiliation, which traveled and changed alongside our practice as exhibition-makers, while we also attempt to map some of the personal, methodological, and theoretical territories that they transverse in the history of natural history. While we focus on avifauna to keep a certain narrative coherence, our broader objective is co trouble the image of Nature that the natural history museum is designed to produce; the need to contest this image of Nature, which is still so readily and casually inherited-even amidst an anthropogenic, planetary mass-extinction event-is, for us, a political act. Indeed, as Razmig Keucheyan has convincingly argued in Nature is a Battlefield, “Nature is not somehow free of the power relations in society; rather, it is the most political of allentities.” 7 Understanding how images of

Nature have been conceptualized and produced by Western coloniality/modernity matters, because, again and emphatically: “Nature is not natural.” 8 In fact, as we hope to demonstrate in this essay, the image of Nature at stake in museums of natural history today is neither natural nor neutral; instead, depending on how concepts of necroaesthetics and humiliation are negotiated in and among these spaces, museums can either reinforce exterminist and colonial projects of domination or participate in decolonial practices of mulrispecies solidarity

and survival.

The Ornithologist, the Taxidermist, and

the Plume Boom

Birds of paradise were represented as ethereal and alluring inhabitants of this remote, exotic land—indeed, part of the treasure the island promised. Collectors' cabinets, oil paintings, and illustrated books worked together in depicting the birds as sublimely sensuous and beautiful. [...] The deaths of the birds and the violence involved in transforming living birds into skins and plumes were sublimated within the language and logic of fashion and science.

—Rick De Vos, “Extinction in a Distant Land” 9

In the history of natural history, birds and taxidermy share a long legacy that is indelibly connected to the colonial control of land and resources. Yet, despite rampant colonial domination, the homegrown desire to view “exotic” productions of tropical nature was difficult to satisfy because so few Europeans could afford to travel abroad; meanwhile, the specimens that were captured alive often died in transit on their way back to Europe. In this context, taxidermy became the medium through which the image of tropical nature was produced for a European audience. The early taxidermists experimented most frequently with avifauna because, as Paul Lawrence Farber, a specialist on the history of ornithology, explains:

During the eighteenth century European naturalists and collectors came to possess an enormous quantity of information and material sent back from Africa, Asia, and the New World by explorers. colonists, and professional naturalist-collectors. The resultant, expanded empirical base for natural history raised technical, theoretical, and philosophical problems, and the solutions to thest problems constituted many of the preconditions for the emergence late in the century of specialized disciplines such as ornithology. 10

Birds of paradise were represented as ethereal and alluring inhabitants of this remote, exotic land—indeed, part of the treasure the island promised. Collectors' cabinets, oil paintings, and illustrated books worked together in depicting the birds as sublimely sensuous and beautiful. [...] The deaths of the birds and the violence involved in transforming living birds into skins and plumes were sublimated within the language and logic of fashion and science.

—Rick De Vos, “Extinction in a Distant

In the history of natural history, birds and taxidermy share a long legacy that is indelibly connected to the colonial control of land and resources. Yet, despite rampant colonial domination, the homegrown desire to view “exotic” productions of tropical nature was difficult to satisfy because so few Europeans could afford to travel abroad; meanwhile, the specimens that were captured alive often died in transit on their way back to Europe. In this context, taxidermy became the medium through which the image of tropical nature was produced for a European audience. The early taxidermists experimented most frequently with avifauna because, as Paul Lawrence Farber, a specialist on the history of ornithology, explains:

During the eighteenth century European naturalists and collectors came to possess an enormous quantity of information and material sent back from Africa, Asia, and the New World by explorers. colonists, and professional naturalist-collectors. The resultant, expanded empirical base for natural history raised technical, theoretical, and philosophical problems, and the solutions to thest problems constituted many of the preconditions for the emergence late in the century of specialized disciplines such as

Plate from Étienne-François Turgot, Mémoire instructif sur la manière de rassembler, de préparer, de conserver er d'envoyer les diverses curiosités d'histoire naturelle (Paris, 1758), 55

In other words, the colonial will to knowledge produced a collateral obsession with the classification of living things that relied on the delivery of the dead bodies of birds as study objects.

This necroaesthetic will to knowledge is everywhere in evidence in the colonial archive. One especially compelling document is the Mémoire instructif sur la manière de rassembler, de préparer, de conserver et d'envoyer les diverses curiosités d'histoire naturelle, which we accessed in the Kroch Rare Books Library at Cornell University. Published in 1758 by Etienne-François Turgot, it is the earliest field manual for bird preparation and describes some of the earliest concerns of this scientific-aesthetic mode of re-presentation. Richly illustrated, the publication gives detailed instructions on tools for and techniques of skinning dead birds: a process typically requiring the length-wise cutting of the body to remove the internal organs, then the scraping off of fat from the skin before treating the feathers with spices and various chemicals, and then stuffing the body with a soft material. Alternatively, and depending on the size of the birds, Turgot also suggests placing them in brandy-filled jars or barrels for preservation. 11 Beginning with Turgot, we followed the various technical improvements for conservation as slowly but surely this practice was refined. Thus, as enormous collections were assembled from the colonies, an increasing number of specimens could be kept in a state of suspended decay; and, when the monumental natural history museum exhibitions first opened to their European publics in the nineteenth century, they could present lifelike, mounted specimens holding their postures in countless vitrines and habitat dioramas.

Notably, Turgot was not the only naturalist to contribute to the reordering of Nature in 1758; one of the early Enlightenment's most comprehensive taxonomies of the natural world was also published this year. With the Systema Naturae, Carolus Linnaeus introduced his binomial nomenclature to the world of zoological classification, but he also put it to use, with the author naming many of the species therein himself. Among them was one bird of paradise species, commonly referred to in English as the “greater bird of paradise.” Linnaeus chose the Latin name Paradisaea apoda—translated as the “footless” bird of paradise—in reference to the amputated state in which these dead creatures were traded in Nusantara, and therefore to the form by which the birds were also known in Europe. Since the first bird of paradise skins arrived in Portugal via Magellan's ship in the 1550s, the innovative if entirely false idea had circulated that these extravagantly feathered birds lived solely in the heavens and only fell to Earth when they died; given this divine habitat, they obviously did not require feet. Numerous illustrations by Renaissance naturalists, like Conrad Gessner and Ulisse Aldrovandi, also encouraged this belief, and for over two hundred years not a single European ornithologist contributed any reliable field observations of these particular birds' true habits or behaviors. 12

Notably, Turgot was not the only naturalist to contribute to the reordering of Nature in 1758; one of the early Enlightenment's most comprehensive taxonomies of the natural world was also published this year. With the Systema Naturae, Carolus Linnaeus introduced his binomial nomenclature to the world of zoological classification, but he also put it to use, with the author naming many of the species therein himself. Among them was one bird of paradise species, commonly referred to in English as the “greater bird of paradise.” Linnaeus chose the Latin name Paradisaea apoda—translated as the “footless” bird of paradise—in reference to the amputated state in which these dead creatures were traded in Nusantara, and therefore to the form by which the birds were also known in Europe. Since the first bird of paradise skins arrived in Portugal via Magellan's ship in the 1550s, the innovative if entirely false idea had circulated that these extravagantly feathered birds lived solely in the heavens and only fell to Earth when they died; given this divine habitat, they obviously did not require feet. Numerous illustrations by Renaissance naturalists, like Conrad Gessner and Ulisse Aldrovandi, also encouraged this belief, and for over two hundred years not a single European ornithologist contributed any reliable field observations of these particular birds' true habits or

Illustration of a bird of paradise from Conrad Gessner, Icones Avium Omnium, Quae in Historia Avium Conradi Gesneri Describuntur Cum Nomenclaturis Singulorum (Zurich, 1555). Courtesy of Universitäts und Landesbibliothek Sachsen-Anhalt, Halle.

In the 1820s, when the Frenchman René P Lesson finally witnessed a bird of paradise flying in the canopies of a coastal forest in Western New Guinea, he likened the experience in his ensuing book to seeing “a meteor whose body, cutting through the air, leaves a long trail of light.” 13 This sensational news aroused great attention among many European naturalists and the birds of Southeast Asia quickly became a competitive subject of zoological research. As Rick De Vos has pointed out, the representations of birds of paradise as “ethereal, exotic, beautiful, and seductive” charmed Europeans as they fed their Romantic tropical fantasies. 14

Throughout the nineteenth century, naturalists continued to travel to colonial Indonesia and New Guinea to observe, collect, and ship home birds of

paradise. In the imperial centers of Europe, the effect of these growing collections was both scientific and cultural. Indeed, bird collections in Europe and the United Scates grew rapidly, increasing the demand for previously unseen species to be collected and imported. In the world of popular culture, Victorians fancied their private houses outfitted with glass vitrines of exotic animals—above all, swank and

colorful birds from the tropics. Additionally, a boom in women's bird-hat fashion significantly increased the demand for plumage from Southeast Asia. European milliners soon preferred bird of paradise skins that had been prepared with arsenic by professional collectors to the skins on offer from local

hunters. With such demand, the “plume boom” led imported European firearms to replace bows and arrows in the tropical forest. As demand grew, plume trade businesses operated by Dutch merchants

began to dominate the market in the late nineteenth century, leading to increasing numbers of exports.

In Southeast Asia, the colonial history of bird collecting thus exemplifies one of the contemporary paradoxes of Nature appreciation: that the adoration of tropical wildlife also led to its destruction in vast and rapid numbers while frequently redirecting and

overwriting the many local histories of interspecies relationships. 15 Until various conservation policies were enforced in the 1920s, vast numbers of birds were slaughtered each year, with annual estimates of killed and extracted birds of paradise ranging between thirty to eighty thousand in the late nine teenth and early twentieth centuries. 16 The male

plumes which had evolved over countless generations to entice females to mate, and thus to ensure the

birds' transgenerational existence, had led to

their demise.

Quite Unlike Anything Yet Known

I have a new Bird of Paradise! of a new genus!!

quile unlike anything yet known, very curious and

very handsome!!! When I can get a couple of pairs, I will send them overland, to see what a new Bird of Paradise will really fetch. I expect £25 each!

—A. R Wallace, letter to Samuel Stevens 17

While traveling among the Aru and Molucca Islands, Wallace obtained skins of five of the now scientifically identified forty-two bird of paradise subspecies. His role as a collector is preserved in the scientific name Semioptera wallacii, or Standardwing Bird-of-Paradise, endemic to the Indonesian “spice islands.” The adult males are brown-and-green breasted with two long-white feathers extending separately from the top of each wing. These individuals are most active in the early dawn hours when they fly from branch to branch, crowing and prancing in the canopies for a willing female mate. For evolutionary biologists, the natural and sexual selection traits of highly individualized island species like the Semioptera wallacii are a beloved object of study.

Almost

every natural history museum in the world proudly exhibits birds of paradise for their most exuberant and diverse adaptation.

During one of our many field visits to Indonesia, we had the rare opportunity to crouch quietly under the forest canopy near Weda on Halmahera, North Maluku province, together with George Beccaloni, the director of the Wallace Correspondence Project. As curators, after seeing countless dead skins in museum collections, the contrast of finally seeing and experiencing these birds alive, performing their erotic forest rituals on their own terms, in their own habitat, was overwhelming. For amateur observers like us, these small, delicate birds are a little difficult to make out among the shadowy foliage and branches, but their desirous calls resound in the jungle. The incredible suspense of waiting to spot a live Standardwing in the slowly brightening forest is a magical thing, which at one point had both of us crawling up a crooked trunk, cheeks against bark, hearts beating rapidly and eyes eager to witness the emerald flickers. 18The humbling privilege of witnessing the birds that morning in the forest transformed our

knowledge about them.

Wallace obtained the first specimens of the

emerald species in October 1858, and he immediately wrote a letter to Samuel Stevens, his London-based agent, relaying the birds' beauty and noting his

expectations for its profitable sale in Europe:

I believe I have already the finest and most wonderful bird in the island. I had a good mind to

keep it a secret, but I cannot resist telling you. I have a new Bird of Paradise! of a new genus!! quite unlike anything yet known, very curious and very handsome!!! When I can get a couple of pairs, I will send them overland, to see what a new Bird of Paradise will really fetch. I expect £25 each! Had I seen the bird in Ternate, I should never

have believed it came from here. so far our of the hitherto supposed region of the Paradiseidæ. I consider it the greatest discovery I have yet made; and it gives me hopes of getting other species in

Gilolo and Ceram. [ ... ] [Bacan] also differs from all the other Moluccas in its geological formation, containing iron, coal, copper, and gold, with a glorious forest vegetation and fine large mountain streams: it is a continent in miniature. The Dutch are working the coals; and there is a good road

to the mines, which gives one easy access to the interior forests. 19

Wallace was instrumental in supplying ornithologists and taxidermists with the bird skins that he

shot or purchased and then shipped home to Europe. What is critical to realize is that the profits generated through these sales of specimens allowed Wallace to finance his collecting, with profits funding further forays in the tropics. This economic dependency, in part, helps to explain the unique enormity of his Southeast Asia collection, amounting to

125,660 specimens.

His role was that of a colonial entrepreneur who ingeniously collected for sale large quantities of

longhorn beetles from the rotting trunks of trees deforested in order to make space for early coal

mines in the north of Borneo, and who approached the birds of paradise via the logging roads beginning to cut through the landscape. 20 His travels and his successes were entangled in the system of coloniality he was a part of; he capitalized on the growing

demand for tropical specimens and, “wherever he went, his safety depended on the protection and

practical infrastructure afforded by colonial political authority.” 21 Indeed, besides their curious aesthetic and zoological value, museum skins are evidence

of the historical infrastructures and trade networks disseminating tropical species from the colonies to collectors and museums in the imperial centers. As Corey Ross observes in Ecology and Power in the Age of Empire:

“Europe's empires created institutions and forms of governance that were specifically designed to travel. They applied technical and scientific

knowledge that claimed universal validity. Perhaps most importantly from an environmental perspective, they assembled markets and transport networks that spanned oceans and continents [...]. Trade links were the vital sinews of European empire, and fom 1870 to 1940 world trade more than quadrupled.” 22

In Southeast Asia, the colonial history of bird collecting thus exemplifies one of the contemporary paradoxes of Nature appreciation: that the adoration of tropical wildlife also led to its destruction in vast and rapid numbers while frequently redirecting and overwriting the many local histories of interspecies

I have a new Bird of Paradise! of a new genus!! quile unlike anything yet known, very curious and very handsome!!! When I can get a couple of pairs, I will send them overland, to see what a new Bird of Paradise will really fetch. I expect £25 each!

—A. R Wallace, letter to Samuel

During one of our many field visits to Indonesia, we had the rare opportunity to crouch quietly under the forest canopy near Weda on Halmahera, North Maluku province, together with George Beccaloni, the director of the Wallace Correspondence Project. As curators, after seeing countless dead skins in museum collections, the contrast of finally seeing and experiencing these birds alive, performing their erotic forest rituals on their own terms, in their own habitat, was overwhelming. For amateur observers like us, these small, delicate birds are a little difficult to make out among the shadowy foliage and branches, but their desirous calls resound in the jungle. The incredible suspense of waiting to spot a live Standardwing in the slowly brightening forest is a magical thing, which at one point had both of us crawling up a crooked trunk, cheeks against bark, hearts beating rapidly and eyes eager to witness the emerald

Wallace obtained the first specimens of the emerald species in October 1858, and he immediately wrote a letter to Samuel Stevens, his London-based agent, relaying the birds' beauty and noting his expectations for its profitable sale in Europe:

His role was that of a colonial entrepreneur who ingeniously collected for sale large quantities of longhorn beetles from the rotting trunks of trees deforested in order to make space for early coal mines in the north of Borneo, and who approached the birds of paradise via the logging roads beginning to cut through the

Bird skins collected in Southeast Asia by Alfred Russel Wallace now belonging to the Museum Heineanum, Halberstadt, Germany. Installation view from “Disappearing Legacies: The World as Forest," Natural History Collections, Martin Luther-University Halle/ Saale, October 20-December 14, 2018. Photo: Michael Pfisterer. Courtesy of Anna-Sophie Springer and Etienne Turpin.

In the case of Wallace's Malay collection, letters and specimens were either dispatched to London for delivery by the faster overland route (partly by camel via Suez and Alexandria to Malta) or went along the slower sea route around South Africa. 23 Upon arrival, specimens were presented to assemblies of scientists at the London Zoological Society and acquired by the British Museum and other international collectors. 24 Among these was Ferdinand Heine, a German sugar-beet baron with a passion for collecting unusual birds. The third instantiation of “Disappearing Legacies” in Halle included a selection of five bird skins on loan from the nearby Museum Heineanum in Halberstadt, where curators had just rediscovered nearly two hundred original “Wallace specimens” by analyzing the labels and sales records of Mr. Stevens. Throughout the exhibition cycle, these bird skins were the only original Wallace specimens we presented; they demonstrated the German collectors’ keen interest in Wallace's journeys, which they followed closely from afar, as paying customers eager for new objects and knowledge.

The afternoon after our jungle birding experience, still reveling in what we had seen, we picked up Wallace's Malay Archipelago and reread a passage reflecting on his initial encounter with birds of paradise in the wild, and which includes some of his most melancholic deliberations. On the one hand, Wallace assesses the existence of birds of paradise as a unique outcome of long and complex lineages of life and interaction; on the other, he understands his own incursion into the territory as a foreshadowing of the birds' inevitable extermination:

I thought of the long ages of the past, during which the successive generations of this little creature had run their course

—year by year being born. and living and dying amid these dark and gloomy woods with no intelligent eye to gaze upon their loveliness: to all appearance such a wanton waste of beauty. Such ideas excite a feeling or melancholy. It seems sad that on the one hand such exquisite creatures should live out their lives and exhibit their charms only in these wild, inhospitable regions, doomed for ages yet to come to hopeless barbarism; while on the other hand, should civilized man ever reach these distant lands, and bring moral, intellectual and physical light into the recesses of these virgin forests. we may be sure that he will so disturb the nicely-balanced relations of organic and inorganic nature as to cause the disappearance, and finally the extinction, of these very beings whose wonderful structure and beauty he alone is fitted

to appreciate and enjoy. 25

Remarkably, Wallace recognizes the cascading ecological effects of extinction events while admitting he is part of the cause. To be attentive to the “collective death” that characterizes these events, present-day environmental philosopher Thom van Dooren suggests thinking of species not as individualized “life forms” but as forms of life that are irreducible to mere population numbers and data. 26

It is both remarkable and depressing to recognize the extent to which debates and awareness regarding biodiversity loss have changed since we began the project in 2013. In fact, as we were writing this text, an article in the New Statesman suggested that we should no longer speak of “climate change” but “environmental breakdown,” while newspaper headlines about the disappearance of insects and birds appear almost daily 27 In Germany, large-scale agriculture and excessive use of pesticides have all but eradicated the habitat of once familiar insects, reducing their overall biomass by sixty percent since the early 1980s—the brief time span of our own lives. Against this background, we feel compelled to challenge dominant systems of productivity and accumulation while participating in movements for social and environmental justice.

Following the work of Boaventura de Sousa Santos in The End of the Cognitive Empire, we believe such a shift entails recognizing the thinking-feeling, affecting body—human and nonhuman—as both

a sensor and agent of knowledge, politics, and community. Attuning ourselves to zebra finches, canaries, and birds of paradise helps to remind us of something elementary: in the words of de Sousa Santos, our bodies are an “ur-narracive,” “happenings,” and “embodied knowledge becomes alive in living bodies [...] they are the bodies that suffer with the defeats and rejoice with the victories.” 28 Within our current extinction crisis, when sixty percent of

all mammals, birds, fish, and reptiles are estimated to have been lost just since che 1970s, every little bird still alive today is also a kind of victory. 29

Still, the International Union for Conservation of Nature lists the Semiopcera wallacii as “near threatened.” And, while local groups on Halmahera are monitoring and protesting the encroachment on the island's forests by national and international corporations, plantation industries have depleted the landscapes of larger islands, such as Borneo and Sumatra, to such an extent that they are now increasingly prospecting on the smaller islands in the East, as well as in West Papua and Papua New Guinea. 30

A Thousand Names of Empire

Bird-of-paradise is pure masculinity.

—Clarice Lispector, Aqua Viva 31

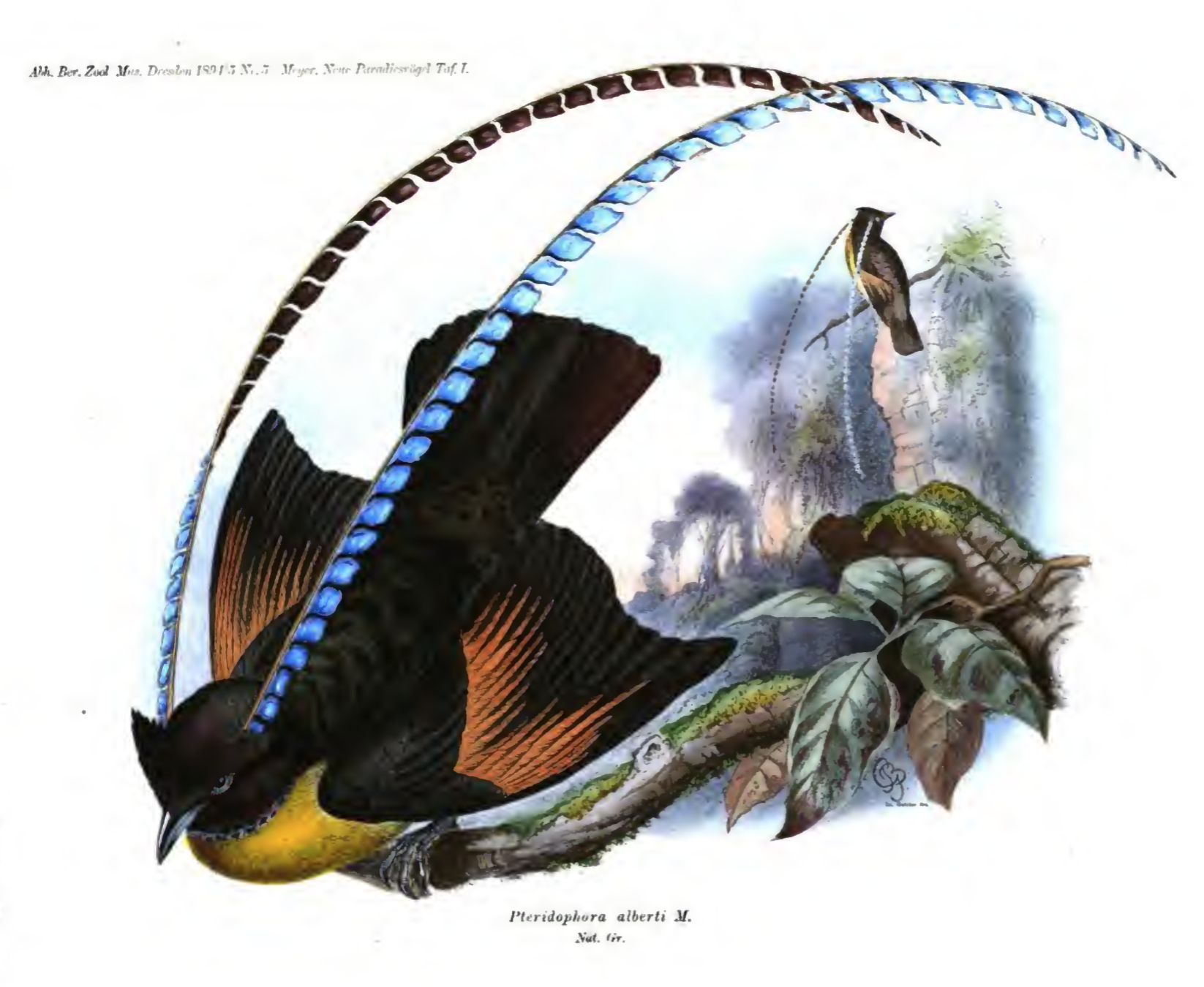

It is not only naturalists who are remembered in the nomenclature of biological species. Paying attention to the names on the labels of animal specimens in the drawers and cabinets of the collections in Hamburg, Berlin, and Halle led us to some crucial political insights about the will to scientific knowledge and class power in the heydays of natural history. For example, in the bird of paradise family, there is the Pteridophora alberti, or King-of-Saxony Bird-of-Paradise, endemic to the Bismarck Mountains in New Guinea. The adult male is characterized by two extremely long “brow-plumes,” which it

can erect from its head at will during its courtship dance. The animal—which the Kundagai Maring people of the area call balpan—received its scientific name in 1894 by Adolf Bernhard Meyer, a German ornithologist and anthropologist, and, from 1874

to 1906, director of the Royal Zoological Museum in Dresden, capital of Saxony. There is also the Paradisaea guilielmi, or Emperor-of-Germany Bird-of-Paradise, a larger bird with bushy yellow plumes that resembles Linneaus‘s P.apoda. A male type specimen of this New-Guinea species was sent to Berlin in early 1888 by German collector Carl Hunstein, and then named in honor of Wilhelm II, King of Prussia, who was crowned the last German Kaiser in the same year.

Presenting “Disappearing Legacies” in Germany made these avian designations narratively pertinent. While the thirty-year period of German colonialism may appear as a brief lapse when compared to the colonial eras of the Netherlands, France, or England, it is impossible to understand German history and identity without accounting for the influence of colonialism and imperialism. 32 In the context of the exhibition, we calibrated our curatorial assemblages on Wallace and the birds of paradise to address the era of German colonization in the Pacific. In a more general sense, the stories that emerged are exemplary for the complicity between imperialist politics, economic interests, and the natural sciences.

Importantly, the imperial names of the specimens are also mirrored on the map itself. The majority of bird of paradise species are endemic to New Guinea; looking at a contemporary map of the island, “Finschhafen” stands out among the other place names in Morobe province on the northeast coast. Both “New Guinea” and “Finschhafen” indicate the nearly five hundred years of colonization on the island. 33 While the Spanish claimed “Nuevo Guinea” in 1545, Finschhafen was founded in 1884, the same year the flag of the German Empire was raised on several other Pacific islands after annexing the land. It was named after Otto Finsch (1839-1917), an ornithologist who in 1884-85 participated in a German colonial mission that occurred under the false pretense of a natural science expedition. 34 While German traders had already established export relations and large-scale plantations on other islands, it was not until Bismarck officially endorsed colonial annexations that overseas expansion became a true state affair. Until the end of World War I, the “German Empire” held as its possessions colomes in Melanesia and Micronesia: the so-called “Kaiser-Wilhelmsland” on the northeast coast of today's Papua New Guinea, several larger islands in the "Bismarck Archipelago," the Solomon and the Marshall Islands, as well as the islands of Samoa, Manus, and Nauru.

During his time in the Pacific, Finsch was an agent of the Neuguinea-Kompagnie, a powerful German trading syndicate attempting to colonize new territories in a region already dominated by the other European powers and the United States

(Hawaii). The Kompagnie was founded in the early 1880s by influential German bankers and trading companies, including Hamburg-based firms such as the Deutsche Handels-und Plantagen-Gesellschaft (DHPG), the Sudsee-Aktiengesellschaft, as well

as Adolph Woermann, then the largest private ship owner in the world. Authorized by King Wilhelm II (1859-1941), the company had the power to directly administer the “Protectorare” with the unambiguous goal of exploiting natural resources in the region for the benefit of the German Empire. 35 The most valuable materials to be extracted from the islands in the Pacific were phosphates and tropical woods, but the development of plantations also allowed for the intensive cultivation of copra, cocoa, coffee, rubber, sisal, and tobacco.

Back in Germany, Finsch frequently collaborated with Adolf Bernhard Meyer, a naturalist based in Dresden. In late 1885, they copublished descriptions of a number of hitherto unknown bird species, including the Paradisaea rudolphi, named as such in honor of Crown Prince Rudolf of Austria-Hungary, a passionate bird enthusiast himself. 36 In our research for the exhibition cycle, Meyer had already come up in a slightly different context than the colonial legacies inscribed in the scientific nomenclature of che birds of paradise. A fluent English speaker, he was also Wallace's German translator and thus had been instrumental to the dissemination of evolution in the German-speaking world. In

1869, he published the German translation of The Malay Archipelago almost in parallel with the original English edition; in 1870, his translation of the Darwin-Wallace texts on the origin of species and evolution from 1858 followed, including his own commentary on the matter; and, in 1875, he successfully solicited to translate also Wallace's then still forthcoming book On the Biogeographical Distribution of Animals. 37

For “Disappearing Legacies,” episodes of Meyer's biography became important connecting threads for understanding Wallace's legacies in German natural history institutions. Indeed, Meyer's views and field research destinations seem significantly influenced by his familiarity with Wallace's ideas. Alongside Otto Finsch, he was among the very first Germans to visit New Guinea and they are both listed in Wallace's tench edition of The Malay Archipelago (1890) as belongmg to the “most important natural history travellers” following in his wake. 38 Lesser known is the fact that, during his career as museum director, Meyer was also eager to improve the conditions of his bird collection with the result of developing one of the iconic features of natural history museums. Together with the metal fabricator August Kühnscherf & Söhne, he designed a steel-and-glass museum case that made its tropical contents virtually inaccessible to European pests. The so-called Dresden Case became a best seller.” 39

The Interpretation of Imperial Dreams

Man, in his orderly isolation, hardly knows how to react. This is not the doing of Man, He says. But then, what is it, and who will stay alive?

—Anna Tsing, “Earth Stalked by Man” 40

As the Dresden Case enabled the hermetic display of natural history collections for the public and quickly became an iconic technology for viewing the necroaesthetic presentation of tropical taxidermy displays and dioramas, the significance of museum collections for the production of scientific knowledg in Europe was also being further elaborated.

PICTURE

In his essay “On the Physical Geography of the Malay Archipelago,” Wallace describes the role of collecting, and the museum collection, with particularly noble aims:

An accurate knowledge of any group of birds or of insects, and of their geographical distribution, may assist us to map out the island and continents of a former epoch: the amount of difference that exists between the animals of adjacent districts being closely dependent uron preceding geological changes. By the collection of such minute facts alone we hope to fill a great gap

in the past history of the earth as revealed by geology, and obtain some indications of the existence of those ancient lands which now lie buried beneath the ocean and have left us nothing but these living records of their former existence. It is for such inquiries the modern naturalist collects his materials: it is for this that he still wants to add to the apparently boundless treasures of our national museums, and will never rest satisfied as long as the native country, the geographical distribution, and the amount of variation of any living thing remains imperfectly known. He looks upon every species of animal and plant now living as the individual letters which go to make up one of the volumes of our earth's history; and, as a few lost letters may make a sentence unintelligible, so the extinction of the numerous forms of life which the progress of cultivation mentably entails will necessarily render obscure this invaluable record of the past. It is, therefore, an important object, which

governments and scientific institutions should immediately take steps to secure, that in all tropical countries colonized by Europeans the most perfect collections possible in every branch of natural history should be made and deposited in national museums, where they may be available for study and interpretation. 41

The study and interpretation of these vast tropical collections involved two related but distinct procedures: first, the scientific research of curators in the museum that advanced the biological knowledge of the natural world; and, second, the presentation of this research to a public audience, in the form of the museum displays that both justified collection process and advanced an appreciation of Nature and its driving process of invention, evolution. Between the front-of-house display and the back-of-house research collection, a circuit of affective valorization bound these two elements

of the museum together.

Yet, for all the pedagogical good intentions, we believe it is necessary to ask what the image of Nature on offer in the natural history museum obscures. How does a cultural program of human exceptionalism (anthropo-supremacy) become instantiated in museological scenography, narrative, and display? How do museums of natural history reinforce and reify biologically-informed ideas of human exceptionalism? What scenes, sleights, and normalizing gestures subtend this scientific-aesthetic agenda? As we approach such questions and attempt to engage them through our exhibition-making,

we have been informed by and repeatedly returned to a rather extraordinary passage in Sigmund Freud's lectures, A General Introduction to Psychoanalysis. Specifically, we have reflected on Freud's contention that humanity has been subject to

three historic humiliations:

The first was when it realized that our earth was not the center of the universe, but only a tiny speck in a world-system of a magnitude hardly conceivable; this is associated in our minds with the name of Copernicus [...]. The second was when biological research robbed man of his peculiar privilege of having been specially created, and relegated him to a descent from the animal world, implying an ineradicable animal nature in him: this transvaluation has been accomplished in our own time upon the instigation of Charles, Darwin, Wallace, and their predecessors, and not without the most violent opposition from their contemporaries.

His argument continues as he introduces the consequence of psychoanalysis:

Man's craving for grandiosity is now suffering the third and most bitter blow from present-day

psychological research which is endeavoring to prove to the ego of each one of us that he is not even master in his own house, but that he must remain content with the veriest scraps of information about what is going on unconsciously in his own mind. 42

While much more could certainly be said of the first and third humiliations, for our purpose here it is the Darwin-Wallace humiliation that beckons further attention. Indeed, the “humiliation” of evolution as it pertains to the origin story of the human species undermined any other claims to Man's God-given dominion over the natural world. It was simultaneously a profanation of the species and a demotion in rank, but the compensarory response has yet to be fully understood. Even after years of working in the collections in order to actively intervene in and augment the narratives

of these museums, it was only standing in the shared courtyard of Halle—between the natural history museum and the church—that we first understood the implication of this claim. If dominion over Nature could not be maintained through the theological register, wherein Man is given a divine right to Nature, it could still be won by other means, namely, the technological re-presentation of dead Nature as if it were alive and well-composed. Through his spectacular artifice, man could re-present Nature better than Nature could present itself, and thereby instaurate an institutionally-sanctioned psychosocial remedy—a form of collateral domination by way of technologies of necroaesthetic representation. For this reason, we might say that every image of Nature is an image of Man, just as every natural history museum is, upon closer inspection, a museum

of Man. If the natural history museum is a public institution whose remit is nominally the secular celebration of Man's place in the natural world, it is striking that perhaps nowhere is the humiliating origin of the species more repressed.

Still, the International Union for Conservation of Nature lists the Semiopcera wallacii as “near threatened.” And, while local groups on Halmahera are monitoring and protesting the encroachment on the island's forests by national and international corporations, plantation industries have depleted the landscapes of larger islands, such as Borneo and Sumatra, to such an extent that they are now increasingly prospecting on the smaller islands in the East, as well as in West Papua and Papua New

—Clarice Lispector,

Back in Germany, Finsch frequently collaborated with Adolf Bernhard Meyer, a naturalist based in Dresden. In late 1885, they copublished descriptions of a number of hitherto unknown bird species, including the Paradisaea rudolphi, named as such in honor of Crown Prince Rudolf of Austria-Hungary, a passionate bird enthusiast

For “Disappearing Legacies,” episodes of Meyer's biography became important connecting threads for understanding Wallace's legacies in German natural history institutions. Indeed, Meyer's views and field research destinations seem significantly influenced by his familiarity with Wallace's ideas. Alongside Otto Finsch, he was among the very first Germans to visit New Guinea and they are both listed in Wallace's tench edition of The Malay Archipelago (1890) as belongmg to the “most important natural history travellers” following in his

—Anna Tsing, “Earth Stalked by

PICTURE

In his essay “On the Physical Geography of the Malay Archipelago,” Wallace describes the role of collecting, and the museum collection, with particularly noble aims:

The study and interpretation of these vast tropical collections involved two related but distinct procedures: first, the scientific research of curators in the museum that advanced the biological knowledge of the natural world; and, second, the presentation of this research to a public audience, in the form of the museum displays that both justified collection process and advanced an appreciation of Nature and its driving process of invention, evolution. Between the front-of-house display and the back-of-house research collection, a circuit of affective valorization bound these two elements of the museum together.

Yet, for all the pedagogical good intentions, we believe it is necessary to ask what the image of Nature on offer in the natural history museum obscures. How does a cultural program of human exceptionalism (anthropo-supremacy) become instantiated in museological scenography, narrative, and display? How do museums of natural history reinforce and reify biologically-informed ideas of human exceptionalism? What scenes, sleights, and normalizing gestures subtend this scientific-aesthetic agenda? As we approach such questions and attempt to engage them through our exhibition-making, we have been informed by and repeatedly returned to a rather extraordinary passage in Sigmund Freud's lectures, A General Introduction to Psychoanalysis. Specifically, we have reflected on Freud's contention that humanity has been subject to three historic humiliations:

His argument continues as he introduces the consequence of psychoanalysis:

Illustration of Pteridophora alberti from Otto Finsch and Adolf Bernhard Meyer, Zwei Neue Paradiesvögel (Berlin, 1895). Courtesy of Dresden University Library.

1865-7914 (New York: Peter Lang, 2013). ︎︎︎

Strachey (London: Hogarth Press, 1953-74), 285. ︎︎︎